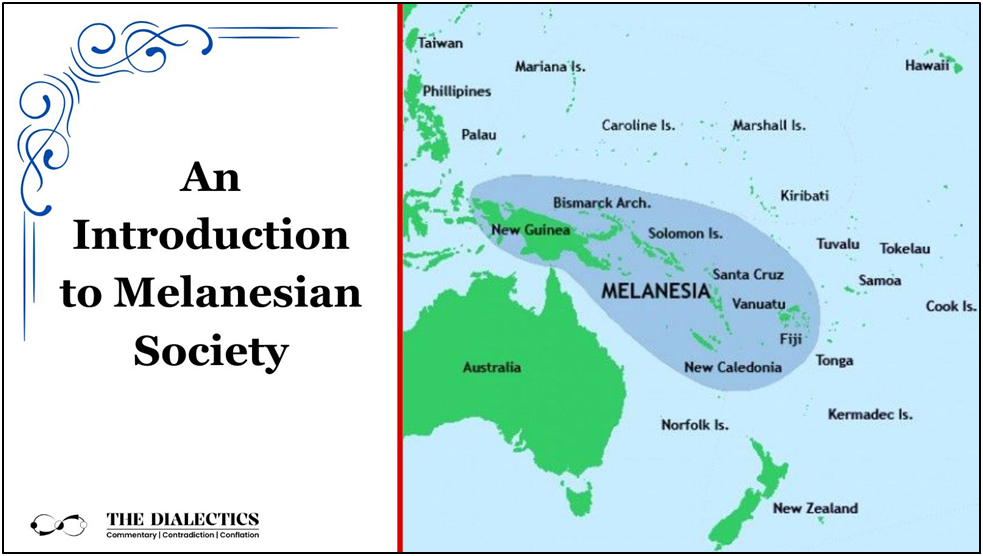

Introduction to Melanesian Culture and People

In the words of Edward B. Tylor, Culture is that complex whole that includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society. The term “Melanesian” refers to the Indigenous people of Melanesia, a region in the southwestern Pacific Ocean that includes New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji and New Caledonia. Carleton S. Coon when explaining the origins of the Melanesian peoples and culture describes that the inhabitants of Australia and the Pacific Islands belong to the Australoid subspecies, evolving from the Pithecanthropoids of Southeast Asia. Before the end of the Pleistocene, Australoids migrated to New Guinea and Australia. During the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods of Southeast Asia, four racial types emerged: Australoids, Mongoloids, Melanesians who represent a mixture between Australoids or Negritos with the invading Mongoloids, and Negritos a dwarfed Australoids or sometimes a dwarfed Australoid-Mongoloid blend. Moreover, the Neolithic sea-faring people of mixed Australoid-Mongoloid ancestry settled in Micronesia, they mixed with the local Pleistocene inhabitants, forming the modern Melanesians. The Negrito people of Melanesia likely developed their small stature on the islands.

Perceptions of Melanesian Societies by Europeans.

The mapping and naming of Oceania as Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia were undertaken by Europeans. In mapping Oceania, Melanesia was the only subregion named after the skin colour of its inhabitants: “the black-skinned people” or “black islands.” The term Melanesia was derived from the Greek word, melos meaning “black” and “nesia” comes from the Greek word nesos, which means islands. According to Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, the geographical mapping of the region was also a racialist mapping. The term Melenesia was deployed to invoke “blackness,” reflecting discourses about race in Europe that categorised human beings worldwide within a racial hierarchy that placed “white” people at the top and the “black” people at the bottom (Kabutaulaka 2015: III). Furthermore, Kabutaulaka discusses Dumont’s views on the Melanesians which comprises the people with very dark, often sooty, skins, sometimes almost as black as that of the Kaffirs, and curly, fuzzy, fluffy but seldom woolly hair. Their features are disagreeable, with uneven build, with limbs often frail and deformed.

Hau’ofa described Melanesian polities as “underdeveloped” and “backward” compared to advanced Polynesia. He argued that Melanesian leaders have a genuine interest in the warfare of their people. Melanesian society has presented a very wry face when viewed as an abstract system of rights and duties or groups and categories, grounded in kinship. Melanesian society argued Peter B. Huber, is ritually constituted through the production of events that mobilized people in a certain way. These events however are not necessarily characterised by inutility or supernaturalism they are not ritual in that sense, but by the fact that they are informed by a scheme of “symbolic classification.” Melanesian polities did not resemble the models of the centralised state that were established in Europe. Kabutaulaka argues that European description of the Melanesian socio-political organisation as “underdeveloped” and “backward” stemmed from their inability to understand the complexities of these societies. For instance, the Kula Ring in Papua New Guinea involved interactions among different language groups, including trade, politics, ceremonial exchanges and social relationships that sustained these societies for thousands of years. Similarly, the shell-money trade between the people of Langalanga Lagoon in the Solomon Islands and Bougainville, and other parts of Papua New Guinea, operated largely outside state control despite regulatory efforts. Early European visitors were likely baffled by the unfamiliarity of Melanesian societies, leading them to employ pseudo-evolutionary ideas placing the European social organisation at the top and the unfamiliar system at the bottom.

(Kabutaulaka 2015).

Kula Ring: A ceremonial Exchange System

The Kula Ring is a complex system of ceremonial exchange practiced in Melanesian societies. It involves around 18 island communities off the northeast coast of New Guinea, which engage in periodic exchanges of shell valuables (vaygu’a): arm shells (mwali) and necklaces (soulava). These items are conceived as “female” and “male” respectively, with necklaces flowing clockwise and armshells counter-clockwise around the ring. An exchange is considered complete or a “marriage,” when a necklace is given for an armshell and vice versa. The process involves an opening gift (vaga) and a delayed restoration gift (yotile) or returning items. In the Trobriands, economic exchange doesn’t enter the ceremonial exchange but runs parallel to it. Moreover, here, the participation is monopolised by the chiefs. While in Dobu, the exchange is more egalitarian. These valuables are ranked but not haggled over; emphasizing personal equivalence rather than market value. Unlike barter, Kula exchange operates alongside economic activities without merging with them. The circulation of these items boosts individual prestige. (Hage, Harary, and James 1985: 108)

Languages of Melanesia

The languages of Melanesia are categorised into two main groups: Austronesian and Papuan (or non-Austronesian). Austronesian includes many Melanesian languages and some Polynesian speakers, while Papuan languages are diverse and often unrelated to each other. These non-Austronesian languages are primarily found in Western Melanesia, such as New Guinea, New Britain, and the western Solomon Islands. Most researchers believe that early settlers from the Asiatic mainland introduced these languages to Melanesia, spreading across the eastern islands.

Capell (1962) argues that Austronesian languages originated from the Asiatic mainland, evolving into proto-Indonesian, proto-Melanesian, and proto-Polynesian. He suggests that different groups of Austronesian speakers left the mainland at various times, with Melanesian languages arising from mixing with non-Austronesian languages, and Polynesian languages resulting from a later migration through Melanesia.

Grace (1964) supports the idea that Southeast Asia was the original homeland, with Austronesian speakers spreading throughout Indonesia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Melanesia by 1500 B.C. He posits that Fijian-Rotuman-Polynesian languages differentiated from the central New Hebrides languages.

Dyen (1965) classifies most Austronesian languages into a Malayo-Polynesian family, suggesting they originated in Melanesia, specifically in the Banks and New Hebrides Islands. He proposes a series of migrations that distributed these languages across the Pacific, potentially starting before 2500 B.C.

Melanesian traditional religion

Melanesians cannot be defined by a single way of life or belief system. However, various groups exhibit similar patterns in their social, political and religious behavior. The religion in Melanesia is a system of belief and practices that help communities understand, explain, and validate the origin and existence of the world, its resources, powers, laws and techniques. These indigenous beliefs and practices are referred to as “Melanesian traditional religion.” Religion is central to Melanesian life, influencing activities such as gardening, hunting, fighting, childbirth, and even death. It permeates every aspect of life, creating a holistic view where there is no division between secular and sacred, animate and inanimate, living and dead. Melanesian culture integrates economic, political, technological, social, and religious aspects into a cohesive system. Life is viewed as an interconnected whole rather than separate compartments. Melanesian traditional religion is a pragmatic, materialistic system that seeks to manipulate spirits and powers for the tangible, this-worldly benefits of the community, such as material wealth, fertility, health, power and prestige. Robert Glasser notes that the historical context and substance of religious life, belief and ritual in pre-colonial Papua New Guinea were characterized by change, fluidity, and movement (Rowsome 2001: 37).

Whiteman argues that the central value of Melanesian religion is cosmic life and renewal. At the heart of all belief and activities is the continuation, protection, maintenance and celebration of life. This “good life” is measured by tangible elements such as great feasts, fertility, the health of children, and the strength of individuals. In Pidgin, all these elements are encompassed by the term “kago” (cargo), symbolising the ultimate expression of abundant life. Strelan describes this “cargo” as including money, freedom from work-related pressures, the regaining of status and dignity, and the effortless acquisition of knowledge and power (Strelan 1977: 70). Abundant life, therefore, signifies harmony, peace, unity, social justice, freedom from oppression, wholeness, restoration, security, and abundance – the desired “gutpela sindaun” (good life). This ideal life is only possible when relationships with others, nature and the supernatural are in balance, symbolised by wealth and the abundance of cargo. According to Schwartz, Cargo symbolises the actions of supernatural powers to deliver people from perceived evils and renew their world.

Significance of Mana in Melanesian belief

Additionally in Melanesia, the concept of Mana is integral to understanding ideas of abundant life, cargo, and salvation. As described by Codrington in his study of the Melanesians, mana is a non-physical, supernatural power or influence that manifests in physical force or any form of excellence a person possesses. Mana isn’t fixed in any object but can be transferred through various mediums, like water, stones or bones. Spirits and supernatural beings inherently possess mana and can impart it to others (Rowsome 2001: 39).

Role of Malangan Art

Malangan art is a traditional art form from Papua New Guinea. It showcase the wooden carvings, masks, and sculptures created for use in ceremonial events, particularly those honoring the deceased. The carvings and masks are often symbolic, representing ancestors, spirits and various cultural myths. Susanne Küchler provides a detailed exploration of Malangan art. According to Kuchler, Malangan art involves creating sculpture described as “tetak,” which means the dissecting and joining of skins. The sculptures represent “skins” that replace the decomposed bodies of deceased individuals, providing a container for their life force, known as “noma.” This life force, captured in Malangan art gives power to the living, which becomes a source of political authority. This authority is derived from controlling the re-embodiment of remembered imagery into new sculptures. The right to reproduce these images is transacted during ceremonial exchanges that accompany the sculptures’ display.

Furthermore, Susanne Küchler explains that Malangan art serves as a model of social immortality, illustrating how social reproduction remains independent of the uncertainties of marriage, birth, and death. By absorbing these events into cultural reproduction, the process redefines continuous situations that introduce discontinuities into social relations. As a model and medium of social reproduction, Malangan art plays a crucial role in the manipulation and legitimization of inter-generational and inter-group relationships.

The destruction of sculptures immediately after their ceremonial display reflects this cultural simulation of social reproduction processes. Just as the human body decomposes after death to release its force, the sculpture is “killed” in ceremonial exchange to release its force into people and new sculptures. In this society, the memory of the sculpture, rather than the object itself, holds value. This memory is used in disputes over land and resources and in legitimizing political authority. Value is attributed to the memory of the imagery and the right to reproduce it, which is transacted in exchanges.

The highest value is given to a form of ownership called “wun in e Malangan” or “the source of Malangan,” which allows the owner to produce an infinite number of sculptures. The term “source” can also be translated as “womb” and “smoke,” alluding to the reproductive capacity surrounding this ownership. The acquisition of this reproductive capacity is embedded in an exchange called “sorolis,” which relates parts of the same matrilineal clan from different residences. Other restricted forms of reproductivity are transacted in “aradem” exchanges, which link affinal matrilineal clans with a history of intermarriage and co-residence. (Küchler 1987: 240)

“The term ‘Melanesia’ is a partly geographic, partly cultural referent to a subregion of the island that has become very much part of ordinary descriptive language along with terms categorizing parts of the Pacific island world, namely Polynesia and Micronesia,” observes historian Stephanie Lawson. The territories of Melanesia have been under the control of six metropolitan governments and two other powers, Japan and the United States, during the brief but crucial period in the 1940s. The western half of New Guinea was part of the Netherlands Indies until 1949, then known as Netherlands Nieuw-Guinea, later Papua Barat, until 1962. The western part was initially divided between Britain and Germany in 1883, then administered by Australia in part as a direct colony and in part as a mandated territory under the League of Nations, and is now under unified administration as the Territory of Papua and New Guinea Melanesia is marked by rich cultural traditions and varied languages, shaped by centuries of history and colonial influences. Both matrilineal and patrilineal systems are present here. The mixture of cultural practices, from the Kula Ring and Malangan art to the deep-seated religious beliefs, speaks to the rich life that defines the Melanesian way.