Since when did Indian women started wearing Blouse: A Sociological Perspective

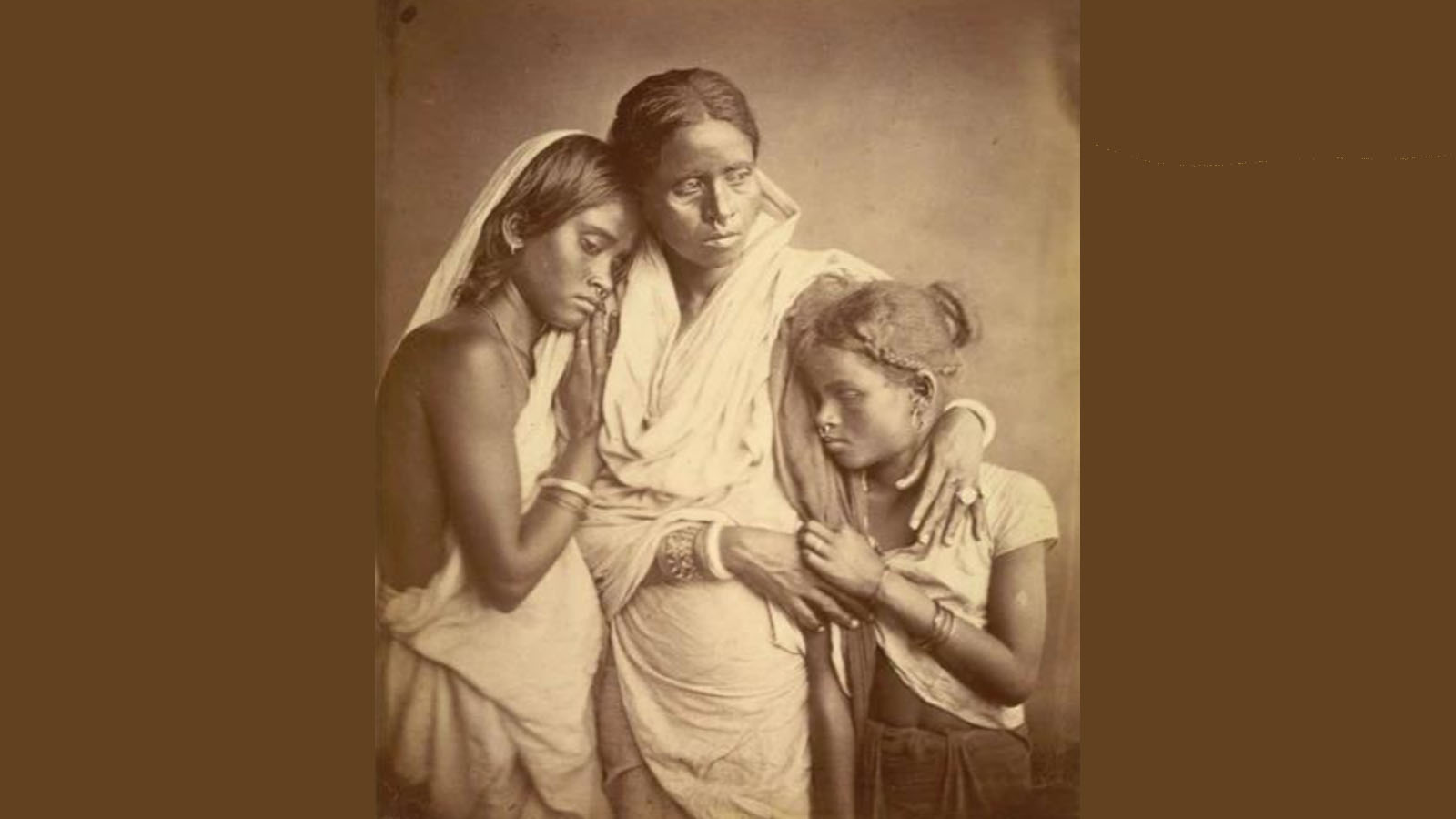

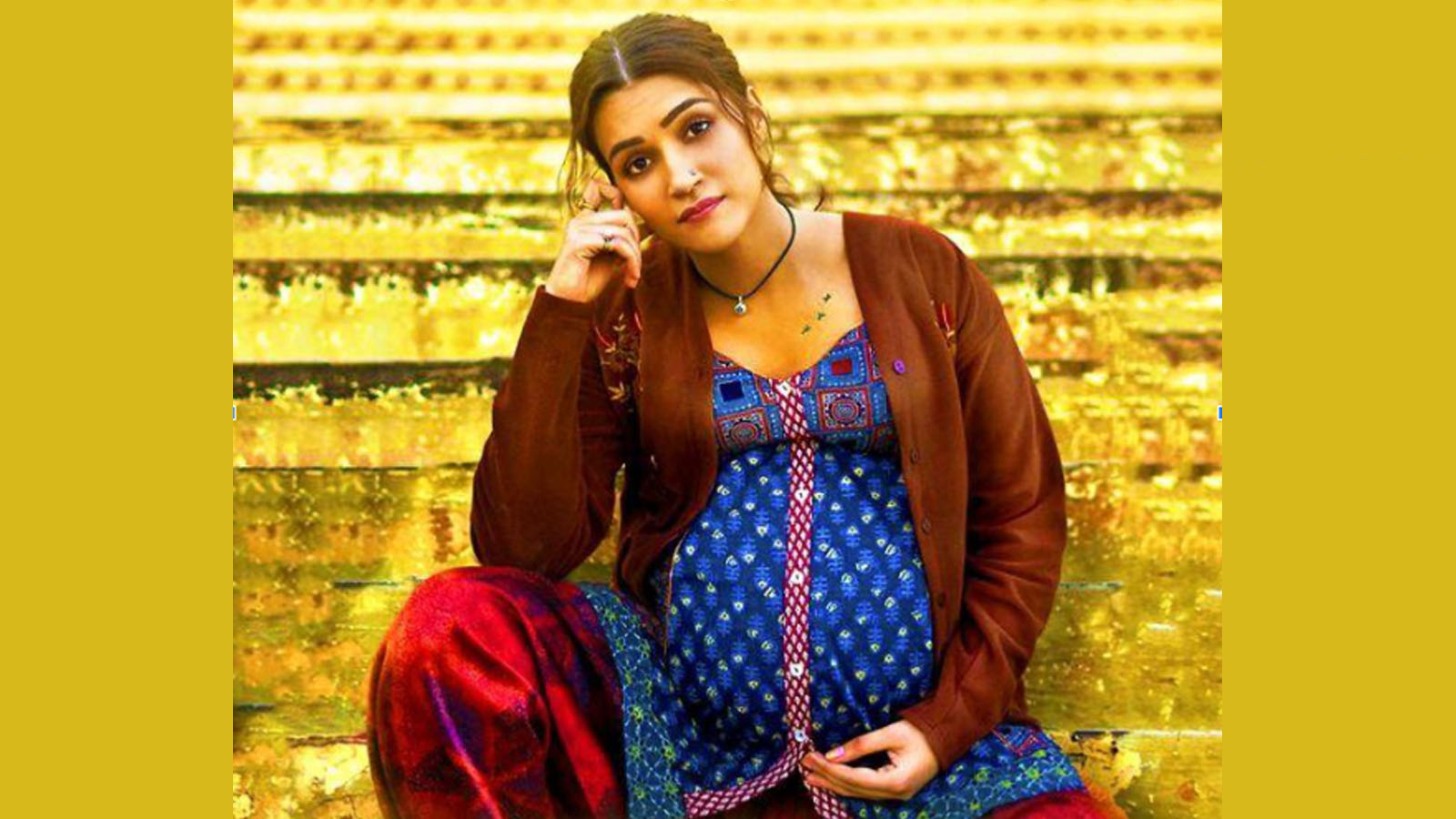

Human cultures evolved through a continuous exchange of ideas, belief, habits, and forms. Dressing habits in particular constitute a fertile plain in which this exchange takes place. The traditional attire evolved over centuries, reflecting religion, ethnicity, geography, cultures, climates as well as communities in India. This essay paints a picture of clothing during the colonial period in India. Before the advent of Europeans Vastra is a Sanskrit term meaning a cloth or a garment. The term holds a significant cultural and historical importance in India. In fact, every region in India has its own distinct clothing styles. Although most of the figures and sculptures in India suggest that clothing in general was scanty. Nudity did not bear a sense of indecency. Women wearing a blouse with a sari had only become known after the 10th century but more defined during the British rule in India. But why did the attire of Indian women change? It was because the British came up with the notion of ‘shame’. They considered exposure to be inappropriate according to their European standards. This led to the encouragement of women adopting a more covered attire to fit with the imposed colonial norms of modesty. From Unsewn to Sewn clothes – Sari’s Colonial turn Saris specifically, differing in terms of fabric, draping style, and decorative elements. The cultural contact between India and British regarding the clothing styles can be divided into the Company period and British rule in India. During the company period, the influence of clothing style travelled more from India to England. Specifically, the Chintz prints which were adopted for full gowns. Whereas during the nineteenth century people began adapting Western clothing. It was the wealthy Parsi community that first took up to adapt the British attire. Women and men traditionally wore unsewn cloths. It was a common practice among the ordinary people to wear unsewn garments like langota, dhoti, gamucha, lungi, turban and the draped sari for women. The change started within the aristocrats, high ranking Indian officials and men from wealthy families. Women wore the choli a sewn blouse or a petticoat, which they removed while cooking food as cooking had to be done in a specially designated and ritually cleansed area of the house. Wearing well stitched blouses, corseted blouses were some of the distinctions introduced to it. Materials like chiffon and lace began to be used for saris and were sometimes added with brocade work to create an Anglicized look. Saree and Nationalism After 1905, the import of British-made cloth into India and the destruction of traditional handicraft production became a theme of protest in Indian nationalism. Clothing became a symbol of national identity. Women became a repository of tradition. Sari was central to the nationalist narrative. It was used to construct the image of the proper Indian woman in the early twentieth century. The popularisation of a national ideal of femininity based on tradition was advanced through the printing press and the paintings of Raja Ravi Varma. Similarly, in a booklet of cartoons on Swadeshi, published in Allahabad titled “Avoid Wasteful Expenditure” portraying a Hindu “mother” dressed in a hand-woven sari explicitly targeting women in India. Anasuya Sarabhai in London Sari – Blending tradition and Modernity One of the prominent figures in evolving attire was Anasuya Sarabhai (1885-1970), who was involved in the women’s suffragette movement and later women’s labour movement, often wore a sari but uniquely paired it with a shirt and a necktie instead of the blouse. Similarly, Maharani Indira Devi of Cooch Behar, influenced by her frequent visits to the Parsis, came across the French Chiffon. She wore it as a sari, stitched with a plain Banarasi border stitched onto six meters of Chiffon, leading to the creation of Chiffon Sari. Additionally, Vijay Lakshmi Pandit, dressed in sari preferring long sleeved blouses with a mandarin collar and a brooch. Maharani Indira Devi of Cooch Behar by Philip Alexius de László. Clothing in India underwent remarkable changes during the British period. Men began wearing trousers, shirts, and suits, whereas women of higher status incorporated blouses, petticoat of different styles into their wardrobes. However, when the Satyagraha movement began, clothing became a significant symbol of resistance and identity. The sari in particular, held immense importance representing cultural heritage and nationalism. In the nationalist discourse, women were expected to support men leading the fight against colonial rule. It was imagined as ‘Bharat Mata’ the ideal mother. The Mother Indians sari was seen as a symbol of the nation, protecting it from the influence of English mill-made fabrics and colonial rule. Today we still find echoes of these clothing styles in various communities across India. For example the Bhotia, Banjara, Lamabada, Sugalis, Lamanis etc continue to wear their traditional clothing. These communities serve as a living reminder of how historical and cultural identities can coexist with contemporary fashion trends.