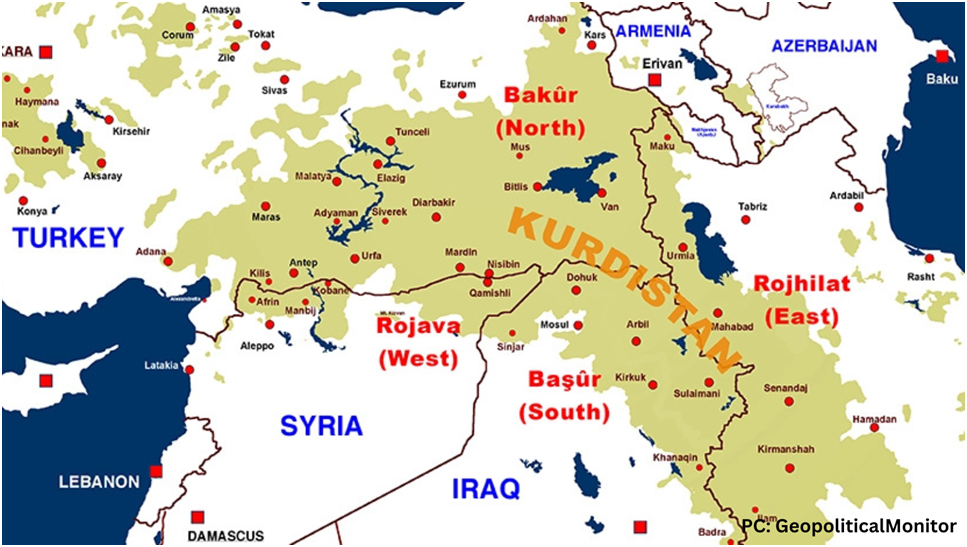

The Kurds are one of the largest ethnic groups in the world without a state of their own. Their population, estimated between 35 and 40 million, is spread primarily across a region historically referred to as Kurdistan, which stretches over parts of southeastern Turkey, western Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syria. Beyond these territories, large Kurdish communities have also taken root in Europe and other parts of the world due to conflict, displacement, and economic migration. This article will discuss how the Kurdish story is one of deep historical roots, cultural complexity, and political marginalization. From ancient highland tribes to medieval dynasties and semi-autonomous provinces under Ottoman rule, the Kurds have long occupied a crucial yet often overlooked position in the geopolitics of the Middle East.

BACKGROUND

Tracing Kurdish origins is a complex endeavor. Some scholars connect them to ancient tribes such as the Carduchoi groups known to inhabit the rugged highlands of the northern Zagros Mountains. Carduchoi were a group of warlike tribes residing in present-day Turkey These tribes were renowned for their fierce independence and played roles in resisting imperial expansion, such as the campaigns. Although many Kurdish tribes resisted early Muslim incursions, they gradually converted to Islam and were incorporated into the broader Islamic world. Before this, however, Kurdish belief systems were rooted in pre-Zoroastrian traditions, reflecting their long-standing presence in the region. Although the majority of Kurds identify as Sunni Muslims, the community is far from religiously homogenous. Substantial minorities follow Shiite Islam and several heterodox or pre-Islamic faiths, including Alevism and Yazidism. Linguistically, the Kurds speak Kurdish, an Indo-Iranian language closely related to Persian. However, the Kurdish language is far from unified. It comprises multiple dialects—chief among them Kurmanji and Sorani, that differ enough to be mutually unintelligible in many cases. These linguistic divisions reflect the diverse and often mountainous geography of Kurdistan, which historically fostered strong local identities. The first identifiable Kurdish dynasties under Islamic rule emerged between the 10th and 12th centuries. Among the earliest were the Hasanwayhids, Marwanids, Rawadids, and Shaddadids dynasties that managed to exercise regional authority.

STRATEGIC ALLIANCE BETWEEN THE OTTOMANS AND THE KURDS

A landmark moment in Kurdish history came with the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, when Kurdish leaders allied with the Ottoman Empire in its struggle against Safavid Iran. It was during this battle that the Kurds and the Ottomans collaborated for the first time and defeated the Safavid dynasty under the leadership of Idris Bitlisi from the Kurd’s side and the Ottoman’s side led by Sultan Salim 1. In exchange for Kurds’ loyalty, the Ottomans granted them leaders a measure of autonomy. This arrangement allowed Kurdish emirs to govern their territories with considerable independence, collecting taxes and maintaining internal order. This autonomy persisted for centuries and was formally acknowledged in works such as the Sharafnameh, a detailed chronicle of Kurdish dynasties published in 1597. However, the relative freedom Kurdish leaders enjoyed under Ottoman rule began to erode during the 19th century. The empire, weakened by territorial losses and facing internal dissent, embarked on a series of centralizing reforms aimed at consolidating its power. These efforts collided with entrenched Kurdish authority, notably that of Mir Bedir Khan—a Kurdish ruler who resisted Ottoman demands and was ultimately deposed by the central government.

NASCENT STRANDS OF NATIONALISM

Traditionally, the Kurds dwelled in the peripheral regions of the Ottoman Empire which was demarcated as the Kurdistan Eyalet (or the Kurdistan Vilayeti) that functioned as a substantial buffer for the Ottomans against their belligerent neighbours, precisely the Persian Qajar. Over the four centuries of Ottoman rule over Kurdistan, their interaction remained mostly cordial yet a few currents of confrontation and conflict persisted. The genesis of a nascent conscious ‘Kurdish Nationalism’ was apparent in the mid 19th century when Ottomans were keen on centralizing the power amid the inception of Tanzimat reforms (launched in 1839 to deal with external as well as internal turmoil which afflicted the Empire). These reforms weakened the autonomy and power of the Kurdish tribal leaders. Concurrently, the antagonism persisted following the ratification of the Treaty of Berlin which was signed on 13th of July, 1878 by the Ottomans that granted protection to the Armenian and other Christian communities, convincing the Kurds that neither Ottomans nor the external powers were concerned about the Kurdish grievances.

In retaliation, a revolt was orchestrated by Sheikh Ubeydullah in 1880-1881 against the Qajars of Persia, who were substantially weak at that point and it was also politically demonstrated against the Ottomans which exhibited their dissatisfaction with the Empire. This episode is often remarked as the onset of Kurdish Nationalism as it demanded an independent nation-state for Kurds and seeked recognition for being distinct from the Ottomans. Ubeydullah was popularly recognised as Sayyid Ubeydullah of Nehri descending from the influential Kurdish Semdinan family and his appeal was influential as a leader of the Naqshbandi sufi order. At the onset of this revolt, he penned a letter to William Abbott, the then British Consul General in Tabriz, where he remarked the Kurds as a ‘People apart’ and a ‘Nation apart’ from the Ottomans. Initially, they managed to seize considerable tracts of northwestern Iran, however, they were soon neutralized by collective military efforts of Ottomans and the Qajars. Later Ubeydullah was exiled to Hejaz.

Another impetus followed, when Kurds colluded with the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) and other Ottoman subjects who grew wary of autocratic policies of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Soon after, an edict was circulated in November 1890 for the formation of the Hamidiye Light Cavalry who were solely trained to serve the Sultan. This came amid apprehension of looming Russian threat and potential internal upheaval. But above all, it was the calculated and concealed effort of the Ottoman Empire to re-assert their influence over the erratic Kurds to utilize them as vanguard defenders against the belligerents of the Sultan. Simultaneously, it intended to keep the Kurds fragmented as it was majorly composed of Sunni Kurdish tribal forces who were pitted against the Alevi Kurds along with Urban-Christian Kurds, which polarised them and this undermined the nationalistic fervours among Kurds.

Their national consciousness gained traction again in the early 20th century with the inception of Young Turk Revolution (in 1908) which liberalised the political atmosphere making it conducive for Kurdish nationalist aspiration that led to the foundation of the Kürt Terraki ve Teavun Cemiyeti also known as the Society for the Mutual Aid and Progress of Kurdistan (SMPK). It advocated for educational reforms and modernisation of Kurdish society. Along with, it endorsed the circulation of newspaper ‘Kurdistan’ in Istanbul which was published by the descendants of Prince Bedir Khan (who launched an uprising against the Ottomans in 1847). This paper was first issued on 21 April 1898 (in Cairo) in Kurmanci dialect which was essential in disseminating the nationalist fervours among the fragmented Kurdish populace. However, this society was outlawed in 1909 by the Ottomans. Simultaneously, other publications floated like the Teraki newspaper (essentially a weekly Journal), Roji Kurd (a monthly journal), Hetawi Kurd (much like an editorial compilation) and Yekbun ( Journal) throughout the early 20th century.

In around 1914, a couple of rebellions erupted in Barzan and Bitlis province, but they were swiftly subdued by the government. Soon after, another formidable society was budding by November 1917, i.e. the Kürdistan Teali Cemiyeti, or the Society for the Advancement of Kurdistan (SAK). It was formally established in December 1918 and was headquartered in Istanbul. Another seminal impetus to the Kurdish statehood reverberated in Jan 1918 following Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, which in its 12th statement precisely noted about the opportunity of an ‘autonomous development’ of other (non Turkish) nationalities present under Ottoman command. Subsequently, the Ottomans assented to the Mudros Armistice on 30th Oct, 1918 against the Allied forces which led to their political dissolution in November, 1922.

DECISIVE TREATIES

The pioneers of SAK remained assertive about an independent Kurdish state in the eastern regions of Anatolia and they rigorously reiterated the stipulations of Treaty of Sèvres. This treaty was signed on 10th of August, 1920 among the Allied powers and the Ottoman Empire which incorporated a delegation from SAK that lobbied for an independent Kurdish state. Consequently, as delineated in Article 62 (and the couple of consecutive articles) that the establishment of an independent Kurdistan for the Kurdish people which shall be recognised by the League of Nations subsequently. This idea of Autonomy was also reaffirmed at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 where there was an unified consensus regarding non Turkish Ottoman subjects shall be granted the ‘opportunity of autonomous development’. It was the foremost instance of international recognition of the Kurdish aspiration towards Statehood.

Albeit such a robust endorsement for a potential Kurdish state; their dreams remained unrealized as this treaty was never ratified by the Turkish Grand National Assembly which deemed it as an embarrassing settlement. Mustafa Kamal Atatürk repudiated it and orchestrated a resistance against the Ottoman government who conceded to the treaty and led the Turkish war of Independence in 1919 which perpetuated till 1923. Consequently, it re-demarcated the boundaries and abolished the caliphate and marked the advent of a modern Turkish Republic. Moreover, it enacted the Treaty of Lausanne (that superseded the former treaty) which was negotiated in Lausanne, Switzerland, from November 1922 till 24th July, 1923 when it was formally implemented. It consisted of 141 Articles and outrightly omitted the reference of a Kurdish statehood altogether as he asserted a stern stance towards assimilation and centralization of the Republic. Hence, few Kurds were assimilated and others were dispersed across the borders. Their aspirations of a statehood remains un realised and the Kurdish populace lies fragmented mostly among four nations i.e. Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran and a minority resides in south western Armenia. Their plight persists till date as they strive for ‘self determination’ from separate states that seek to curb the creation of Greater Kurdistan.