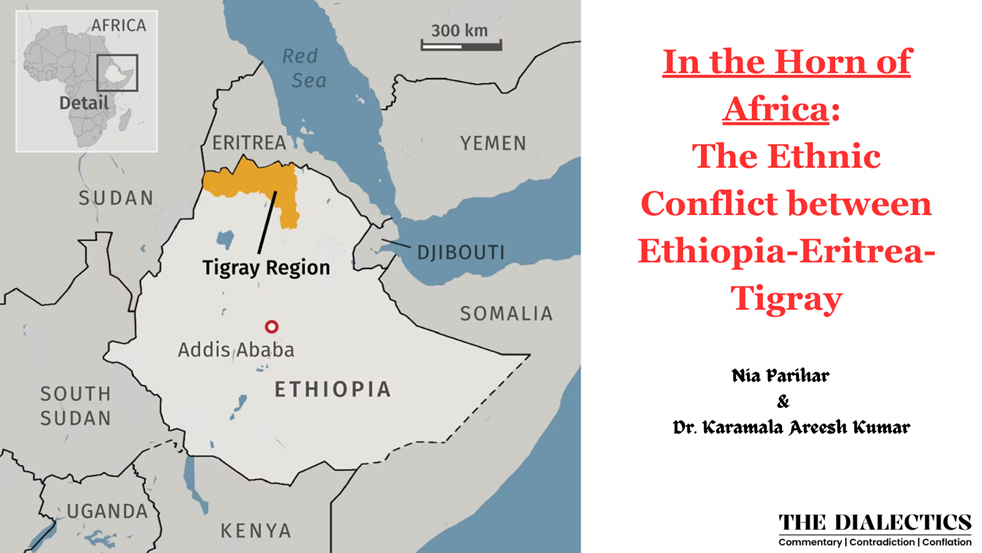

The Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia) has long been a region of geopolitical significance due to its strategic location, diverse resources, and complex socio-political landscape. It is situated at the crossroads of the Middle East and Africa. It controls significant sea routes, including the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, vital for international trade. Additionally, the region is rich in resources, including arable land and minerals, making it a focal point for global interests. However, this region is marked by complex inter and intra-state conflicts. Among the most persistent and impactful disputes in this region is the tension between Ethiopia and Eritrea, which has elevated the conflict in Tigray. This paper thoroughly examines the origins of these tensions, their current state, and the humanitarian and geopolitical impact they continue to generate.

Roots of the Conflict

The roots of Ethiopia-Eritrea tensions date back to the colonial era. Once an Italian colony, Eritrea came together with Ethiopia in 1952 in a federal union under United Nations General Assembly Resolution 390 A (V). However, Emperor Haile Selassie of the Amhara ethnicity (a dominant group in Ethiopia), keen on gaining access to the Red Sea to enhance Ethiopia’s economic and strategic position, annexed Eritrea in 1962, dissolving its autonomy and triggering a long and complex 30-year conflict for independence. Eritrea ultimately achieved independence in 1993 following a UN-monitored referendum, where the majority of Eritreans voted for independence, but the relations with Ethiopia quickly soured.

Border demarcation became a crucial issue for dispute, especially over the town of Badme, which both countries claimed. It sparked the Eritrean-Ethiopian War (1998-2000), which proved to be one of the deadliest wars in that region, with more than 100,000 dead. The Algiers Agreement in 2000, although meant to end the war and establish the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC), left Ethiopia in its refusal to implement the EEBC’s ruling, thereby keeping the tensions high since it fuelled resentment in Eritrea on the failure of territorial resolutions and continued political and military hostilities between the two nations.

In 2018, a landmark peace agreement brokered by Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed offered hope for reconciliation. Abiy’s acceptance of the EEBC’s border ruling earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019. However, the rapprochement, marked by the signing of the 2018 peace agreement and public displays of diplomacy, masked deeper structural issues. These included unresolved territorial disputes and longstanding political mistrust between the nations. Despite the optimism generated by the agreement, the lack of legitimate economic or social integration efforts meant that the underlying causes of tension remained unaddressed. Furthermore, Eritrea leveraged stabilising and improving relations with Ethiopia to consolidate internal control, while Ethiopia faced criticism for failing to implement broader reforms that could stabilise the region.

Tigray’s Appearance

The conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, which began in November 2020, has significantly altered the dynamics between Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which dominated Ethiopian politics for decades, fell out of favour with Abiy’s administration, leading to armed clashes.

The Eritrean military joined the Ethiopian federal forces, supposedly to neutralise the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). Eritrea’s role was significant as it brought a long-standing adversary into the conflict, given the historical tensions between Eritrea and the TPLF dating back to the Eritrean-Ethiopian War of 1998-2000. Their involvement added another layer of complexity to the conflict. On the other hand, Ethiopia’s federal government, led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, launched a military campaign against the TPLF in November 2020 following what it described as an attack on federal military bases by TPLF forces.

The signing of the Pretoria Peace Agreement in November 2022 can be considered a significant turning point in the Tigray conflict. The struggle between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Ethiopian federal government was officially resolved with this accord, which the African Government aided.

Implications of the Conflict

The Tigray conflict has had profound consequences, such as over two million people being displaced and millions facing acute food insecurity. Eritrea’s role has strained its relations with other regional actors and the international community, with its autocratic regime under President Isaias Afwerki facing growing criticism. Reports of atrocities committed by Eritrean troops, including massacres, sexual violence, and looting, have drawn international condemnation. The UN and human rights organisations have documented these abuses, accusing Eritrea of exacerbating the humanitarian crisis. In Ethiopia, the federal structure is under significant strain due to heightened ethnic tensions that threaten national cohesion. Regional security risks are heightened due to cross-border attacks and proxy conflicts. Furthermore, disputes over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia add to the situation’s complexity. The Ethiopian military’s actions have been scrutinised for alleged human rights violations and for contributing to the severe humanitarian crisis in Tigray. The conflict has highlighted deep-seated political and ethnic divisions within Ethiopia and has posed significant challenges to the country’s stability and unity.

International Response

Despite the 2022 peace agreement, the Ethiopian federal government’s relations with the Tigray region remain fragile. The Eritrean forces continue to occupy parts of Tigray, defying calls for withdrawal. Diplomatic relations between Eritrea and Ethiopia have soured, as evidenced by Ethiopian Airlines halting flights to Eritrea.

On the international front, the United Nations and other global bodies have called for accountability for the atrocities committed during the conflict in Tigray and for access to humanitarian aid to areas in distress. Regional actors like Egypt and Sudan keenly follow the situation since they have significant interests in the Nile River and regional stability.

Relieving the Horn of Africa’s tensions requires a multidimensional approach. It is, firstly, an immediate requirement for Ethiopia and Eritrea to engage in political dialogue and resolve the regional and ethnic differences as a first step towards rebuilding stability in the region. Moreover, active involvement of the African Union and the UN is required in ensuring compliance with the peace agreements, providing humanitarian aid, and rigidly holding the perpetrators of the conflict accountable through international mechanisms such as the International Criminal Court (ICC), which prosecutes individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and aggression. Special tribunals, such as those established for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, can also be set up to focus on specific conflicts. Hybrid courts, combining international and national elements, could serve as another option for trying individuals responsible for war crimes. The UN human rights bodies and its special inspectors can examine and report on human rights abuses, influencing international opinion and pressuring states to take required action.