France’s influence in Africa has significantly declined, revealing the parasitic dynamics underpinning its colonial and neo-colonial relationships. Rooted in the slave trade and cemented through exploitative colonial policies, France reshaped African economies to prioritize its industrial growth. This article will delve into the forced labour, land dispossession, and the imposition of monocultures stifled local development while creating deep socio- economic inequalities. Post-independence, the Françafrique system perpetuated French dominance through monetary control (via the CFA franc), political manipulation, and military presence.

The Roots of France’s Presence in Africa

France’s engagement with Africa began during the 15th century with the European incursion into the continent. This era was characterized by the transatlantic slave trade, which devastated African societies as millions were forcibly removed to serve as labour in Europe and the Americas. France’s involvement was especially prominent in regions like Senegal and the Gold Coast, setting the stage for its colonial legacy. By the 17th century, transatlantic trade became an economic cornerstone for France. This exploitation underpinned France’s industrial expansion, laying the foundations for modern capitalism.

The 19th century marked a transition from trade colonialism to industrial colonialism. Africa’s resources became critical to European powers like France, with colonization justified as a “civilizing mission” under the European Enlightenment. This ideology masked systemic racism and violence, as Africans were deemed inferior and colonization framed as a moral imperative. Economically, Africa became a lucrative market for European goods and raw materials. French industrialists exploited the continent’s resources and markets, driving territorial expansion into regions like Gabon and Senegal. By the late 19th century, France controlled an African empire spanning over nine million square kilometers.

However, this vast territory was often sparsely populated, and much of it was economically exploited to enrich French industries at the expense of local development. African economies were reshaped to prioritize European needs. Monocultures of export crops like groundnuts, cocoa, and cotton stifled agricultural diversity, leaving local economies vulnerable. Simultaneously, European monopolies dominated industries, sidelining African entrepreneurs and fostering systemic underdevelopment, the effects of which linger today.

France’s Legacy of Exploitation and the Persistence of Françafrique

France’s colonial policies left profound scars on Africa, both economically and socially. Forced labour, land dispossession, and systemic inequality were rampant. The Congo Basin’s exploitation exemplifies colonial brutality, with forced labour systems causing mass deaths and devastation. France’s approach of direct rule dismantled traditional power structures,

marginalizing indigenous leadership. Unlike Britain’s indirect rule, which preserved native elites, France’s policies entrenched hierarchies and stripped communities of self- determination. Arbitrary borders drawn during the colonial era disregarded cultural and political realities, sowing seeds of conflict that continue to challenge post-independence governance.

Cultural plunder was another hallmark of colonialism. France looted countless African artifacts, many of which remain in French museums despite global calls for restitution. This cultural theft symbolizes the ongoing neo-colonial attitudes embedded in international policies, furthering resentment. Even after African nations gained independence, France maintained influence through the Françafrique system. This neo-colonial network relied on bribery, military interventions, and economic orchestration. While this system wanes as African nations diversify partnerships, France’s retention of territories like Mayotte highlights its lingering colonial mindset. Public resentment toward France’s enduring presence is evident in events like the 2023 Niger coup, where symbols of French colonialism became targets of public anger. Historical atrocities, such as Captain Vouillet’s genocidal expeditions during France’s conquest of Niger, underpin this hostility.

In West Africa, France’s colonial dominance was enforced through brute force. Territories governed under French West Africa were subjected to systemic exploitation, with African soldiers denied French citizenship despite their contributions during World Wars. Post-World War II shifts allowed colonies like Niger to gain political representation, but independence in 1960 did not sever France’s influence. The Françafrique system continued to manipulate economies and governance, sustaining neo-colonial control.

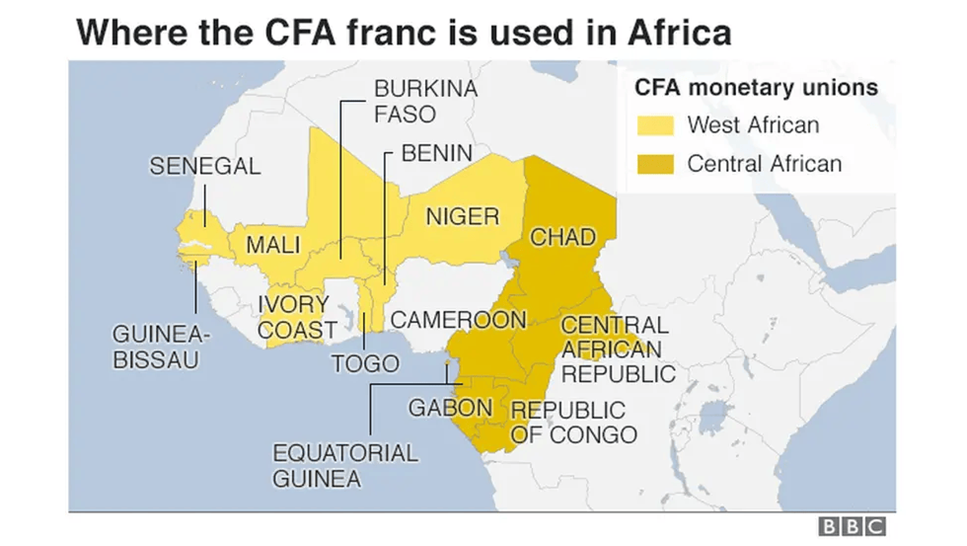

Tied to France: The Economic Realities of the CFA Franc Zone

The CFA franc (Franc of the Financial Community of Africa), established in 1945 under the Bretton Woods Agreement, served as the currency for France’s African colonies. It operates under a fixed exchange rate system, with member countries required to deposit 50% of their reserves into the French central bank. The currency is divided into two zones: the West African CFA (including countries like Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire) and the Central African CFA (including Cameroon and Gabon). Central banks in these zones coordinate monetary exchanges under strict rules to maintain stability, prevent inflation, and guarantee the franc’s value internationally.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, CFA countries benefited from higher GDP growth and lower inflation compared to non-CFA African nations. Cote d’Ivoire, for instance, saw an average annual GDP growth rate of 9.5% between 1960 and 1978, alongside an inflation rate significantly lower than neighbouring Ghana. However, economic shocks in the late 20th century undermined this stability. The overvaluation of the CFA franc and rising deficits led to stagnation, reliance on imports, and fiscal imbalances. The 1994 devaluation, doubling the exchange rate, exacerbated economic hardship, triggering wage freezes, layoffs, and social unrest. This period marked a turning point, exposing the limitations of the CFA franc system in addressing modern economic challenges.

The Decline of French Hegemony in Africa

France’s geopolitical influence in Africa has significantly declined, marked by recent decisions by Chad and Senegal to end military cooperation agreements. Anti-French sentiment is surging, particularly in the Sahel region, where military juntas in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso have expelled French troops. The loss of Chad, a key hub for French military operations, has further weakened Paris’s ability to project power. Many African nations are pivoting toward partnerships with global powers like Russia, China, India, and Türkiye, eroding France’s influence. This shift represents Africa’s move away from historical European ties toward a multipolar world. Despite President Macron’s efforts since 2017 to redefine relationships with Africa through proposals for balanced partnerships and acknowledgment of colonial legacies, progress has been hampered by domestic political instability and inconsistent policies. Failed military operations in the Sahel, such as Serval and Barkhane, and the contentious CFA franc system, which ties African economies to France, have fuelled resentment. Youth-led movements demand reforms or dismantling of the CFA franc zone, while scepticism persists regarding Macron’s proposed economic partnerships and military reforms.

Domestically, Macron’s weakened political standing and a divided parliament complicate foreign policy. Contradictory messaging, including Interior Minister Retailleau’s migration- focused policies and colonial remarks, has further alienated African leaders and citizens.

Conclusion

France’s historical engagement with Africa, rooted in colonial exploitation and perpetuated through the neo-colonial Françafrique system, has left a legacy of systemic underdevelopment and socio-economic inequalities. Framed as a moral obligation to “civilize” Africa, French policies prioritize resource extraction, monoculture economies, and cultural domination, ensuring the enrichment of French industries at the expense of African self-determination. The CFA franc remains a symbol of this economic dependency, perpetuating imbalances and limiting the sovereignty of member nations. Despite gaining political independence, many African nations found themselves entangled in exploitative monetary and political systems that reinforced French dominance. However, the 21st century has marked a turning point, as rising anti-French sentiment and a pivot towards alternative global partnerships reflect Africa’s growing rejection of historical dependencies.