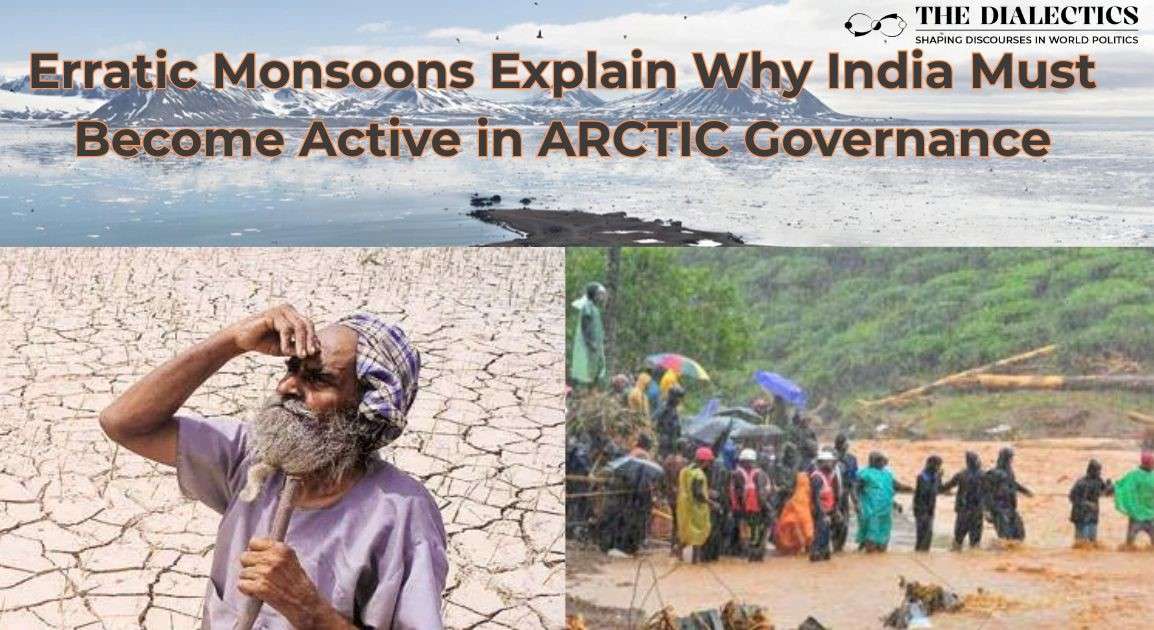

The first monsoon rains that hit Kerala’s shore each year bring more than just rain; they bring the heartbeat of an entire subcontinent. The Indian monsoon is more than just a weather system; it ushers life to the economy, the environment, and the culture. It shapes the future of farming, affects the livelihood of people in rural areas, controls the generation of electricity, and even has an effect on GDP figures. But this easy rhythm is getting harder and harder to predict.

The recent changes in the Arctic and the Pacific Ocean, such as the switch to a La Nina phase, suggest that India’s monsoon may be moving into a new and unstable area. This is not an unlikely scenario. The indications are already visible: more irregular rainfall, shorter bursts of intense downpours, unequal spatial distribution, and increased socioeconomic disturbances.

A Shifting Global Climate Engine

To understand what is happening with the monsoon, one must look outside the Indian Ocean. Over the last two decades, climate scientists have discovered a disturbing teleconnection—a relationship between Arctic warming and shifting weather patterns in Asia. The loss of Arctic sea ice is accelerating faster than expected, weakening the jet stream that normally controls weather systems. This altered jet stream is increasingly meandering, causing extended heatwaves, stalled rainfall systems, and unseasonal extremes.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, ocean surface temperatures are shifting towards a La Nina phase—the chilly sister of El Niño. La Niña is when the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific are colder than normal. Historically, La Niña years have been linked to greater southwest monsoons in India. But the relationship is even harder to understand because of global warming and Arctic amplification.

The India Meteorological Department (IMD) says that the start dates of the monsoon are becoming less predictable. They also say that even though the overall patterns of seasonal rainfall are changing; extreme rainfall events are getting worse. The monsoon in India is in danger because the amount of rain and how it spreads are no longer linked.

La Nina and its evolving complexities

La Niña typically strengthens monsoon circulation, according to traditional climate models. Cool Pacific waters promote cross-equatorial moisture flow, allowing monsoon winds to transport more precipitation to the Indian subcontinent. India’s successful crop years, notably for rice and pulses, have often coincided with La Niña conditions.

India faces mounting systemic risks. A bad monsoon that only lasts a few weeks or happens in a few places can cause flash floods, damage crops, and fill up city drainage systems. In other places, there may be drought. This “wet gets wetter, dry gets drier” pattern makes it even harder for people to get water and for farms to survive.

Arctic-Pacific Feedback Loop

The monsoon is also tied up in a feedback cycle involving Arctic warming and Pacific oscillations. This is how it works. The Arctic is getting warmer about four times faster than the rest of the world. This makes the temperature differences between the poles and the tropics smaller. When the jet stream is weaker, weather systems can stay over places for longer periods of time. This can make heat waves last longer and monsoons start later than they should. La Niña and El Niño change the Pacific Ocean, which in turn changes the trade winds and the temperature of the Indian Ocean. The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) interacts with this, making a complicated dance between three oceans that changes the strength, timing, and spread of the monsoon.

In recent years, this feedback has aligned in unexpected ways. La Nina caused heavy monsoon rains and terrible floods in some parts of India in 2020 and 2021. In 2023, despite La Nina, monsoon rainfall was unequal, with the northeast receiving extra rain and central India experiencing shortfalls. This discrepancy demonstrates how global warming is upending long-held climatic assumptions. India can no longer rely on a consistent La Niña to mitigate rainfall deficiencies.

Economic and social stakes

The altered patterns of the monsoon significantly affect the economy. More than half of India’s net sown land is still used for rain-fed farming, and almost 60% of the people depend on it directly or indirectly. When the monsoon is weak or unpredictable, it makes farming less productive, puts stress on water supplies, and causes food prices to go up.

For instance, in 2022, inconsistent monsoon rains made it hard to grow rice, so the government had to limit exports to keep prices down at home. Similar shortages of pulses and oilseeds caused food prices to go up, which hurt low-income people the most.

But the effects go far beyond farming. When reservoirs don’t fill up again, hydropower generation goes down. Cities are starting to limit how much water people can use. Textiles and sugar are two examples of industries that slow down when they need cooling water or irrigation. The monsoon is more than just a season; it is the basis of India’s economy.

A looming national security challenge

The fact that the monsoon is hard to predict is also a national security issue. Climate change can make it hard for people to farm, get water, and keep their jobs. This can cause people to migrate, which is bad for rural areas and makes social tensions worse. When the monsoons are hard to predict, it’s hard to deal with disasters. India’s disaster management system is getting better, but it still mostly reacts to disasters. A late or hard-to-predict monsoon can cause drought and flooding in many states, which makes it harder to get things done.

The weather has always had a bigger effect on eastern India than on other parts of the country. La Niña and the Arctic getting warmer could change how much rain falls a lot. These problems could make food shortages and competition for resources worse, especially in border areas where politics are important.

Science and Policy Need to Converge

The India Meteorological Department and the Indian Space Research Organization have made progress in predicting the monsoon by using better satellite systems and AI-based models. But just being accurate isn’t enough for a forecast. The integration of climate forecasts into policy is still limited. For example, seasonal monsoon forecasts should have a direct impact on water distribution plans, crop insurance triggers, procurement strategy, and catastrophe readiness. Instead, most efforts are reactive, beginning only after floods or droughts occur.

India needs to take careful steps to handle the La Niña-Arctic risk link. Systems for managing water that can change in real time to keep up with changing rainfall patterns. Some examples of monsoon-tolerant farming methods are growing a variety of crops, using seeds that can survive dry spells, and using precise irrigation. Also, cities should be ready for heavy rain that could cause flooding. Because the effects of the monsoon can be felt across state lines, it is very important for states to work together on water and disaster response.

The Monsoon: A Strategic Climate Asset

Monsoon systems are now seen as strategic climate assets instead of just natural events. For India, keeping the monsoon going means protecting its farming systems, electricity grid, rural economy, and social stability.

This makes climate diplomacy crucial. India must take a more active position in Arctic governance discussions because Arctic warming is no longer a remote Arctic concern but rather an Indian monsoon one. Similarly, Pacific climate monitoring and regional cooperation with countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands can improve La Niña predictions.

Adaptation, Not Just Mitigation

People all over the world are working to slow down climate change, but the changing monsoon shows how important it is to be able to change. India needs to prepare its infrastructure, farming, and disaster response systems for a monsoon season that is less stable and more likely to change. This means spending money on green infrastructure like wetlands, mangroves, and floodplains, which are natural barriers. For example, giving small farmers climate insurance can help make rural economies stronger. Combining the science of monsoons with national planning and using weather data to help the government run smoothly.

The Danger Zone is Here

The warning indicators are no longer subtle. India’s monsoon is being pushed by forces far beyond its borders, from the melting ice sheets in the Arctic to the changing currents in the Pacific. The next La Niña may not be the same as ones from previous years. They might not bring the usual rain, but they could make extremes worse, make inequalities worse, and put even more stress on systems that are already under stress.

The monsoon is getting into a dangerous area, not because it will stop, but because it will become more unpredictable, stronger, and uneven. This is a unique strategic issue for a country that has always depended on its rains to meet its needs. The fundamental question isn’t whether India’s monsoon will change—it already has. The question is whether India’s government, science, and diplomacy can keep up with it.