In the early hours of January 3-4, 2026, the United States breached a line that it had spent decades promising not to cross so brazenly again. U.S. forces launched strikes in and around Caracas and other northern Venezuelan locations, arresting President Nicolás Maduro and First Lady Cilia Flores and transporting them to the United States to face criminal charges, according to sources. Washington’s own rhetoric has been as important as the operation itself. President Donald Trump openly portrayed the action as a political rupture rather than a limited counterterrorism raid or a specific hostage-rescue logic, claiming that the United States would “run” Venezuela temporarily until a transition. Venezuela’s official institutions responded quickly by appointing Vice President Delcy Rodríguez as interim president to ensure administrative continuity following Maduro’s incarceration.

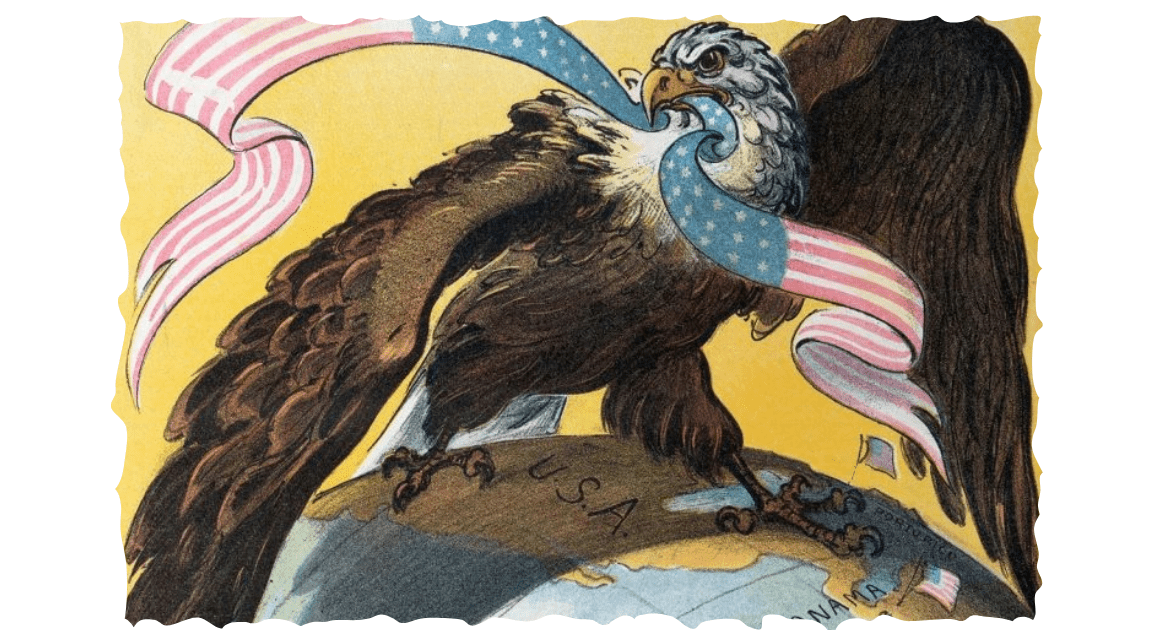

This isn’t only a dramatic episode in Latin America. It is a disclosure event in which the old vocabulary of “restraint,” “norms,” and “rules-based order” gives way to the stark syntax of force. What has ended is not only Maduro’s immediate power but also a broader strategic posture that, despite its hypocrisies, attempted to maintain regime transition deniable, indirect, and cloaked in global process. The message is clearly clear: if Washington determines you are illegitimate, it may no longer bother pretending that the elimination of your government is not the goal.

Operation as doctrine: from pressure to possession

For years, the United States’ strategy toward Venezuela consisted of a range of pressures: sanctions, diplomatic recognition games, asset freezes, international isolation, and assistance for opposition figures. What has changed this week is not only the intensity but also the mode. The transition is from restricting a regime to physically removing its head. Even the public international response has been particularly frank. UN Secretary-General António Guterres cautioned that the US action set a “dangerous precedent,” and a UN Security Council meeting was called to discuss the involvement.

That framing is important because it highlights the true stakes: precedent. When the world’s most powerful state normalizes leader capture and transitional administration by an external entity, it allows for identical logic elsewhere—even if Washington claims its reasons are unique.

Venezuela, for its part, described the operation as “military aggression,” citing attacks in numerous locations and proclaiming a state of emergency state. The key is not to accept Caracas’ words at face value; rather, it is to recognize that once a capital is struck and its head of state detained, the political category shifts. This is no longer considered “crisis management.” This is a political takeover sequence.

The end of strategic restraint means the end of diplomatic theatre

“Strategic restraint” never meant pacifism. It was a power strategy that aimed to keep escalation under control, supported by a coalition, and narratively defendable. It existed because US officials internalized difficult lessons: Iraq’s reputational harm, the quagmires of direct occupation, and the risks of being perceived as an imperial manager.

However, constraint served another purpose: it preserved a plausible pretense that sovereignty mattered. In that story, intervention was rare, lawful, and overseen by the world community. It was always convenient—and frequently abused in practice—but it set a performative limit on what could be done openly. This week, the ceiling collapsed. Trump’s announcement that the United States will “run” Venezuela “for now” does more than just imply a transitional role; it declares tutelage. And tutelage is the language of dominion, not partnership.

Strategic restraint fails when leaders believe that the benefits of shock outweigh the costs of denunciation. The operation reads like a bet that the world is too divided to punish the United States, that allies will complain but adjust, and that enemies will exploit the precedent but be unable to stop it.

The legal question isn’t technical—but political

The legal discussion is already underway, and it will shape how this episode is remembered. The United States has used grounds that critics claim do not satisfy the bar for authorized force under the UN Charter, including the restriction on the use of force except in self-defense or with Security Council authorization. Legal scholars and commentators have largely questioned the operation’s legality, claiming that it resembles an illegal act of aggression rather than a legitimate defensive measure.

The underlying argument, however, is that legality is a battlefield rather than an objective referee. Great powers determine how international law is interpreted and enforced, rather than simply “follow” it. The UN Security Council meeting itself highlights the structural issue: enforcement is subject to veto politics. So the question is, if the costs of illegality are primarily verbal, what prevents repetition?

Venezuela’s institutional pivot: continuity and rupture

Caracas appointed Delcy Rodríguez as interim president through a Supreme Court decree, recognizing the issue as existential rather than episodic. Regime survival is no longer about policing protests or enduring sanctions; it is about preventing administrative collapse and discouraging division within the security forces.

That is the underestimated risk of leader-capture operations: they do not always result in democracy. They can create a vacuum, factionalism, and violence. In many circumstances, the deposition of a ruler hastens struggle among armed actors and political networks for control of the post-leader state.

And because this operation was carried out outside, it exacerbates the legitimacy crisis: any successor authority risks being labeled a proxy, while any internal continuity risks being labeled a junta. Venezuela’s political destiny is currently mired in a narrative conflict: liberation vs abduction, transition versus occupation.

Latin America’s oldest fear has returned

For much of Latin America, US intervention is more than just a historical footnote. It is a lived political memory that includes coups, covert assistance, economic strangling, and military actions. Even leaders who secretly hate Maduro face a public challenge: if this is allowed in Venezuela, who is safe?

Early worldwide reactions were polarized, reflecting the present order’s ideological divisions. However, despite official remarks, the region’s strategic lesson is clear: sovereignty is conditional. The most damaging consequences of this episode may not be what happens in Caracas. It could be what politicians in Beijing, Moscow, Tehran—and in smaller capitals around the world—think about.

If an external authority can seize a sitting president and declare a temporary administration, the category of “unthinkable” diminishes. The argument will be, “If the Americans can do it, why can’t we?”

What comes next: transition, occupation logic, or ongoing conflict?

All of the next steps are uncertain.

- Managed transition (least likely without widespread legitimacy): requires credible Venezuelan actors, regional buy-in, and a defined U.S. leave timeline—all of which have yet to be stated publicly.

- Secondly, proxy governance (more plausible): a US-backed transitional arrangement that struggles for legitimacy and faces armed and political opposition.

- Thirdly, Prolonged instability (most historically consistent): fragmentation, challenged authority, and cycles of violence, particularly when security factions split or external players begin to support rival nodes of power.

The Dialectics point is to avoid predicting outcomes with false confidence. It refers to a structural shift in which a major power has re-legitimized the prospect of direct leader replacement by force, abandoning the previous diplomatic theatre.

Strategic restraint was based on the premise that appearances mattered—that legality, multilateralism, and plausible deniability were not optional. This week implies a different world, one in which power is at ease being naked again.