The use of psychotropic substances like alcohol, cannabis, and opioids has a long history in India, but the current extent and patterns of their use remain poorly documented and regulated. This lack of reliable data has hindered the formulation of effective policies to address the issue of drug abuse. This article examines the magnitude of drug abuse in India, focusing on states with the highest prevalence, trafficking routes and infiltration of global drug cartels. It also examines the state of rehabilitation facilities and identifies best practices that India can adopt to address this escalating issue effectively.

Introduction

“In 2024, narcotics worth ₹16,914 crore were seized, marking the highest recorded value since Independence. The use of the dark web, cryptocurrency, online marketplaces, and drones remains a significant challenge, necessitating strict regulatory measures to address these issues” remarked Union Home Minister Amit Shah.

Drug (substance) abuse has become a worldwide menace. It has become a significant issue, negatively impacting the nation’s physical health and socio-economic stability. India is currently facing a surge in synthetic drug use, with drug abuse reaching alarming levels. The easy availability of these substances in the market poses a grave threat to the population, particularly to the nation’s youth—one of the largest youth demographics in the world—who are especially vulnerable to falling into this destructive cycle.

Drug Abuse Scenario in India

India, with approximately 100 million substance addicts, has experienced a 70% increase in narcotic consumption over the last eight years. The Department of Narcotics Control’s 2023-24 Annual Drug Report states that there were 74,000 drug related cases in India in 2023 and that 98,000 persons were detained for drug-related offenses. Heroin was the most often abused substance among these cases, with codeine-containing cough medication “Phenethyl” and methamphetamine-based tablets following closely behind.

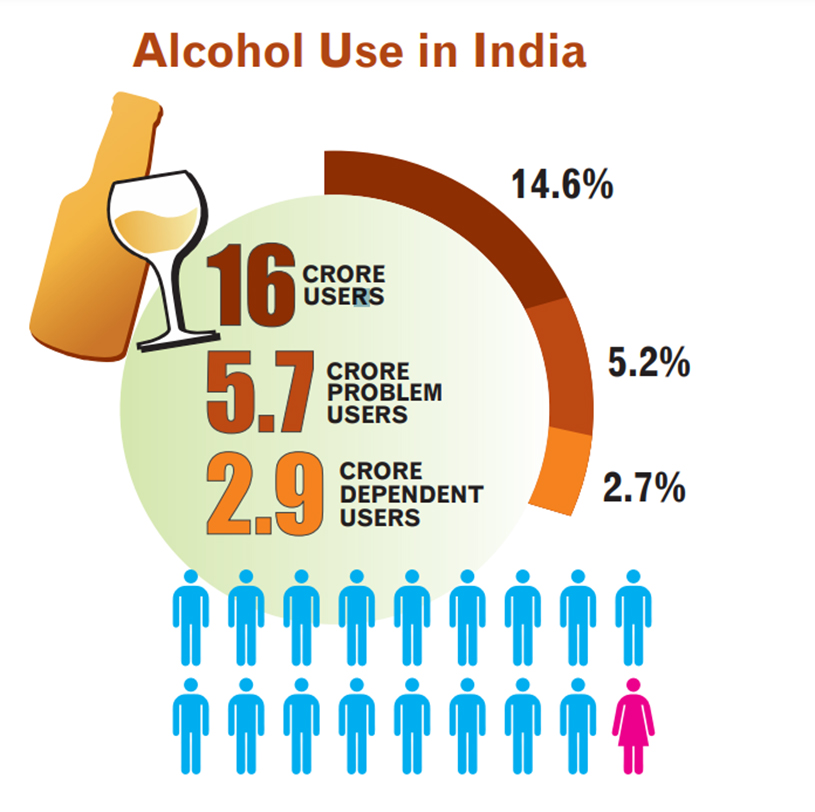

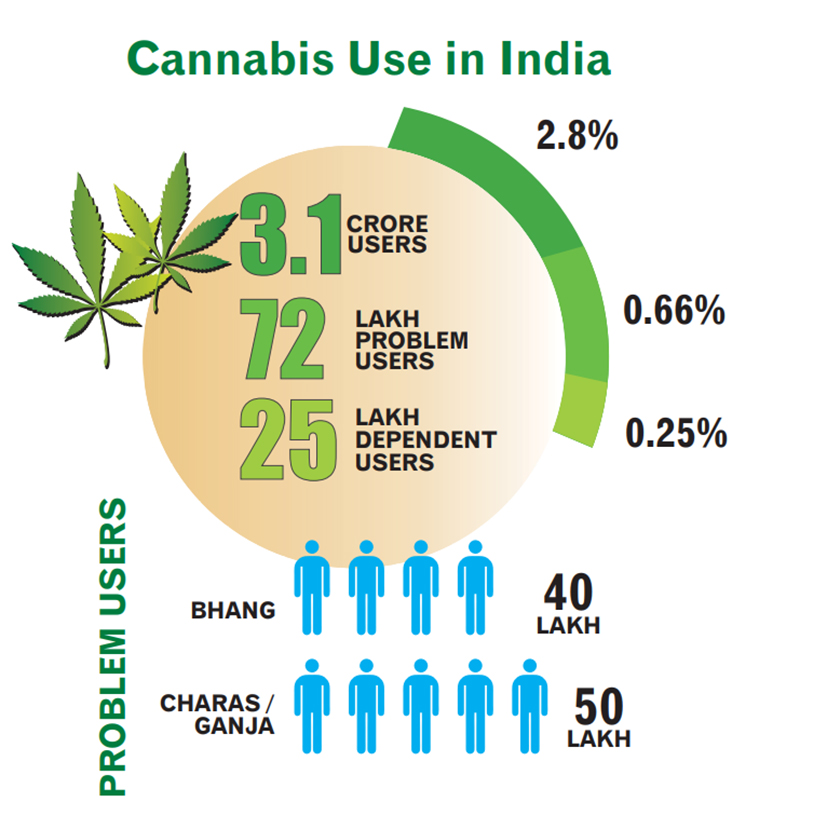

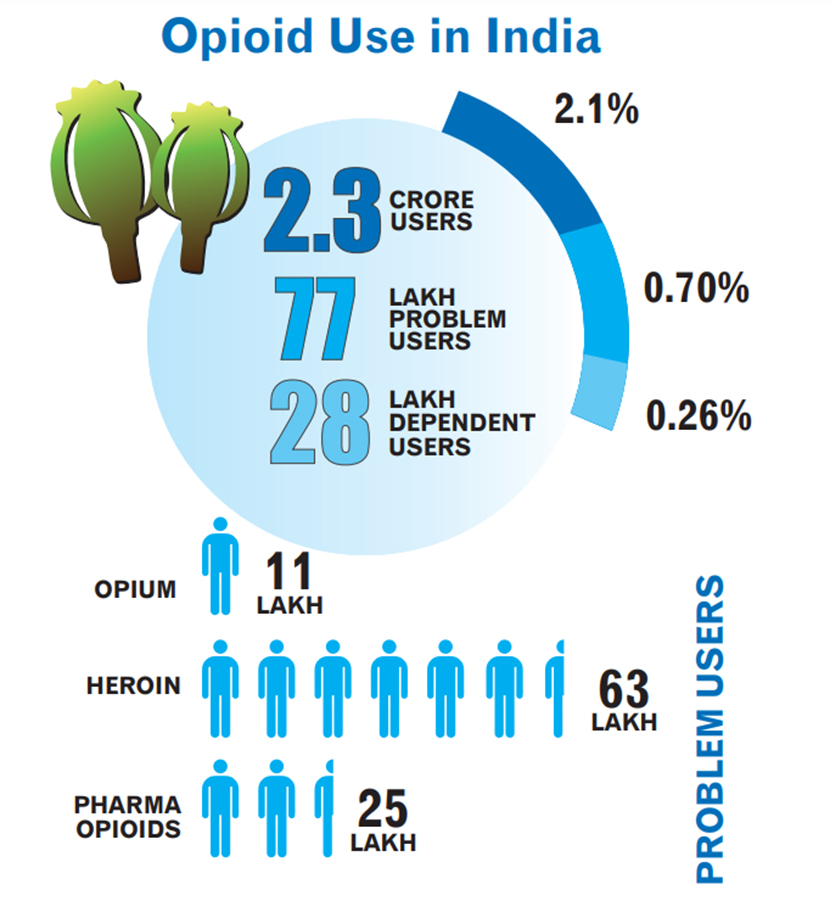

Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment report titled National Survey on Extent and Pattern of Substance Use in India, reveals alarming statistics. Around 16 crore people (14.6%) aged 10–75 years consume Alcohol, with 5.2% dependent. Cannabis users number 3.1 crore (2.8%), with 72 lakh (0.66%) facing cannabis-related problems. Opioid use stands at 2.06%, with 60 lakh (0.55%) requiring treatment.

In India, Cannabis and Opioids are the most commonly used substances after alcohol. Around 2.8% of the population (3.1 crore individuals) report using cannabis, with 2% consuming bhang (legal) and 1.2% using illegal products like ganja and charas. States with the highest cannabis prevalence include Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Sikkim, Chhattisgarh, and Delhi. Opioid use affects 2.1% of the population (2.26 crore), with heroin being the most common (1.14%), followed by pharmaceutical opioids (0.96%) and opium (0.52%). Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, and Mizoram report the highest sedative use.

Sedative use affects 1.18 crore (1.08%), while inhalant use among children (1.7%) exceeds adults (0.58%), leaving 18 lakh children in need of help. Additionally, about 8.5 lakh individuals inject drugs (PWID).

The 2018 survey by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) on drug use among the general population reveals that drug consumption is more prevalent among young people than older individuals. In what is considered a conservative estimate, the UN reports that 13% of drug abuse victims in India are under the age of 20. Safeguarding children from the widespread issue of substance abuse remains one of India’s most pressing policy challenges. However, exceptions have been noted, particularly in the traditional use of substances like opium and khat.

Research indicates that adolescence, ranging from early years (12-14) to late years (15-17), is a high-risk phase for initiating substance use, with usage often peaking among individuals aged 18-25. Social scientists within the country link the prevalence of drug abuse among adolescents to challenging socioeconomic factors such as unemployment, violence, sexual abuse, and exploitation. The majority of drug users came from lower socioeconomic origins; the main risk factors were found to be poverty and a lack of employment prospects.

A 2019 study by the National Institute of Health of 416 high school students in West Bengal revealed a 12.5% prevalence of substance use, higher among urban (15.1%) than rural (10.7%) students. While 73.07% wanted to quit and 57.69% had attempted, “easy availability” and “relief from tension” drove continued use. Awareness of harms was high, with urban students (84.6%) more informed than rural students (61.5%), largely through media. Peer influence played a key role, with 15.4% of urban and 26.9% of rural users encouraging others to start. The findings stress the need for targeted school-based interventions.

Geographical Hotspots

India’s geographic location makes it highly vulnerable to drug trafficking, situated between the Golden Triangle (Thailand, Laos, Myanmar) and the Golden Crescent (Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan). The Golden Triangle is a major supplier of heroin and methamphetamine, with routes entering India through Manipur’s Moreh and Mizoram’s Champai. Similarly, the Golden Crescent impacts states like Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat, with 70% of drugs trafficked via sea routes in the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal.

International drug cartels have significantly infiltrated India. In 2022, the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) busted a cartel linked to Delhi, Rajasthan, Punjab, and Dubai, arresting nine individuals, including three Mexican methamphetamine chemists. In another case, a clandestine methamphetamine lab tied to Mexico’s Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación was uncovered in Greater Noida, leading to five arrests, including a Mexican national. The Delhi Police seized cocaine worth ₹5,620 crore in the largest drug bust in North India. The shipment, originating from Thailand, was intended for high-end markets during festivals and concerts. Additionally, ports like Gujarat’s Mundra have emerged as hotspots for drug trafficking, with a single operation resulting in the confiscation of nearly 3,000 kg of heroin. The shipment originated from Afghanistan and was routed through Iran’s Bandar Abbas Port.

Drug cartels target India’s wealthy clientele, including professionals, businessmen, and students in cities like Delhi and Mumbai, using cryptocurrencies like Tether to avoid detection. Despite significant busts law enforcement faces ongoing challenges in combating drug trafficking due to growing demand, international connections, and sophisticated smuggling networks.

State of Rehabilitation

Numerous obstacles hinder the treatment of drug-involved offenders, including a lack of resources, insufficient infrastructure, and a shortage of trained treatment staff, such as physicians with expertise in addiction medicine, to adequately address the drug treatment needs of those under supervision. Addiction continues to be a stigmatized condition, often not recognized by the criminal justice system as a medical issue. As a result, treatment for addiction is not constitutionally guaranteed, unlike the treatment for other medical conditions.

In May 2018, as part of a lawsuit, the Delhi State Legal Services Authority presented a detailed inspection report to the Delhi High Court, covering 124 de-addiction centers within the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi. The inspection team interacted with 2,135 inmates from various centres and found that 750 of them were involuntarily detained in these facilities. The report also highlighted several other shortcomings, including the absence of basic facilities, failure to maintain patient records, shortage of trained professionals, and numerous violations of human rights.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) launched the Drug De-addiction Programme (DDAP) in 1988 to address the medical treatment of Substance Use Disorders(SUD’s). While the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE) oversees prevention and rehabilitation, the DDAP focuses on treatment by establishing de-addiction centers (DACs) in government hospitals and premier institutions like AIIMS, New Delhi, which was later designated as the National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre (NDDTC).

The program has made significant strides in capacity building, training over 1,000 general duty medical officers (GDMOs), and providing free resource materials for healthcare providers. The Drug Abuse Monitoring System (DAMS), launched in 2007, tracks treatment trends, while Drug Treatment Clinics (DTCs) introduced outpatient care with free psychosocial and pharmacological support funded by the central government. By December 2016, 14 DTCs were operational, with plans for 100 nationwide. Despite early success, challenges persist, including low patient access and retention, staff shortages, inadequate medicines, limited psychosocial interventions, and inconsistent monitoring. Sustained funding and better integration into general healthcare systems are crucial for long-term success.

Portugal’s Pioneering Drug Policy

Portugal’s innovative approach to drug policy, implemented in 2001, which has yielded significant public health improvements. By decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of all drugs, the country shifted from a punitive to a health-centered model. This strategy has been associated with a substantial reduction in drug-related deaths, with the number of heroin addicts decreasing from 100,000 to 25,000 by 2018. A key component of this policy is the establishment of Dissuasion Commissions, which assess individuals found with drugs intended for personal use. These commissions, comprising social workers, medical professionals, and legal experts, determine appropriate responses, such as treatment referrals or fines, rather than criminal prosecution. This approach resulted in a significant reduction in cases of problematic drug use by 2018. Harm reduction initiatives have also played a crucial role. Programs like needle exchange services and supervised drug consumption rooms have been implemented to minimize health risks associated with drug use. These efforts have contributed to a significant decline in HIV infections among drug users, with new cases dropping by 90% since the policy’s implementation. The number of individuals seeking treatment for drug addiction has doubled, reflecting a more supportive environment for those affected by substance use disorders.

Conclusion

The rising prevalence of substance abuse in India poses a critical threat to the nation’s social fabric and economic stability. The issue is compounded by India’s vulnerability to trafficking routes, the growing sophistication of smuggling networks, and inadequate rehabilitation infrastructure. Addressing this crisis requires a multi-faceted approach, including stricter law enforcement, improved access to de-addiction services, and targeted awareness campaigns. Equally important is the need to destigmatize addiction and recognize it as a medical condition requiring sustained care and integration into the healthcare system. Only through collaborative efforts by government, civil society, and communities can India effectively combat the menace of drug abuse.