A quarter (one-third) of the global GDP and more than half (60%) of the world’s population might be accounted for by the massive multi-trillion dollar Belt and Road Initiative, which spans over 71 nations. The concept consists of several marine “roads” and overland “belts” of shipping lines that connect Eastern Africa with South-East Asia. Under the project, more than 2,600 projects have been started in various industries, including telecommunication, energy, and transportation. With a projected $575 billion, China’s Belt and Road Initiative projects in corridor economies aside from China itself will boost commerce between these nations from 2.7% to 9.7% and help 7.6 million people escape extreme poverty. With this project, China wants to increase its soft power in Central Asia, mainly resource-rich in gas and oil.

By strengthening trade, establishing deeper economic relationships, and supplying much-needed infrastructure in poorer countries, China is establishing itself as a worldwide leader. This impact goes beyond economics; by providing finance for essential projects, China enhances diplomatic ties, fosters political goodwill, and increases its strategic and cultural presence in participating nations, particularly in resource-rich Central Asia. However, recently, the BRI has drawn criticism for its impact on Xinjiang’s Uyghur population.

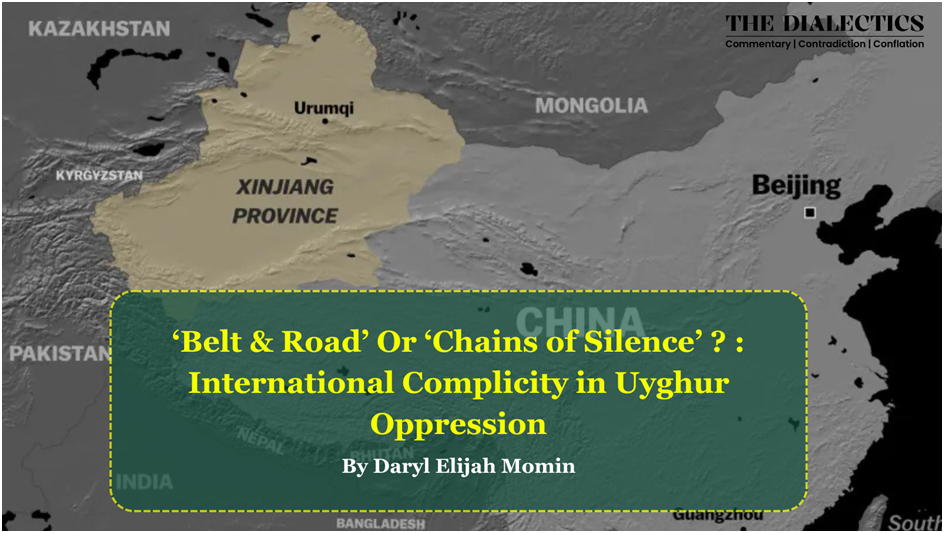

In China’s largest region, Xinjiang, the Uyghurs are a Muslim ethnic minority with a long history that dates back to the first millennium BC, when the Silk Road was at its height. They make up fewer than half of the 26 million people who live in Xinjiang, where they were once the largest ethnic group. The Chinese government’s encouragement of Han Chinese migration to the area, attracted by its mineral wealth and economic potential, marked the beginning of the decrease in the Uyghur share in overall population. The Han Chinese, who make up 42% of the population today, are in charge of Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang.

With its central Asian location as a vital buffer zone connecting China and Europe, the province is strategically significant for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Beyond its physical significance, Beijing wants to attract international capitalists to Xinjiang to make them essential to the region’s growth. As a result of this involvement, foreign stakeholders are encouraged to concentrate on protecting their interests in the region’s resources, trade, and earnings.

The Uyghur Muslims pay a high price for regional development, and the BRI is making it worse for them.

Firstly, the government promotes the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as a means of connecting the Xinjiang area with the rest of the world and portraying the Uyghurs as a people that is prone to extremism and antagonistic to growth and wealth. Giving them this designation enables China to view them as a liability and serves to “justify” the crimes that have occurred in the area. Furthermore, the outcry against the 9/11 attacks has been exploited by the Chinese to view and treat the Uyghurs as a “volatile” and “violent” minority, as they are already proven to be an unavoidable cause of Islamophobia worldwide. On the other end of the scale, attacks on Uyghurs by the security forces are rarely documented. In 2009, Chinese security forces arrested over 1500 Uyghurs in Urumqi, nine of whom were given death sentences. This was an unreasonable and unprovoked reaction.

Secondly, since the family laws were changed in 2017 to permit an equal number of children for all ethnic groups, Xinjiang has been accused of gravely violating reproductive rights. As a result, penalties for policy infractions were increased, and law enforcement actions like coercive sterilisation and IUD insertions were stepped up. Causing birth rates to drop precipitously in certain places by as much as 48%; discriminatory enforcement in areas with a Uyghur plurality has been questioned, and these actions seem to be connected to counter-extremism initiatives. Evidence indicates that Uyghur women were disproportionately exposed to coerced birth control methods, even though the government maintains that these practices are in line with international trends.

The third, and maybe most deadly effect of the BRI on Uyghur Muslims is that the economic advantages it bestows on participating nations subsequently pay for their silence—or rather, a lack of compassion for the suffering of the Turkic-speaking people. The future of its miserable economy depends on the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the building of the Gwadar port complex. Still, Pakistan, a frequently vocal opponent of policies that endanger the lives and dignity of the average Muslim, is silent on the plight of Uyghur Muslims.

Silent Partners and their Selective Amnesia

As China signed a Memorandum of Understanding to join the Belt and Road Initiative, Italy, a nation that stood out against the atrocities committed against the people of Gaza and Ukraine, was noticeably absent from the group of nations denouncing China. In 2023, the European Union abandoned the plan only after announcing China as “a partner, competitor, and systemic rival.” Countries like Kazakhstan and Turkey, which have ties to the Uyghur Muslim community—Turkey shares linguistic and cultural traits with them, and Kazakhstan has seen hundreds of ethnic Kazakhs detained and rounded up in Xinjiang—are also affected by the BRI. Despite these connections, both nations have stated that they have faith in China (since the Kazakh economy is closely tied to their neighbour’s, and Turkey is a strong advocate of the BRI) and that the actions it has taken are essential to preventing terrorism and religious extremism.

Chinese President Xi Jinping compared himself to Zhang Qian, the imperial envoy for the Western Han dynasty, who was once at the forefront of establishing transcontinental connections between Asia and Europe via Central Asia and characterised the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as an ambitious attempt to break the multi-century pause of the ancient Silk Road at the first-ever BRI Forum in 2013. One cannot ignore the part that the emergence of multilateralism has played in this purported Silk Road resurgence, even though these parallel merits greater nuance in and of itself. The UN has been optimistic about the Belt and Road Initiative’s capacity to work since its inception. It views the BRI’s impact on world politics favourably. However, to comply with UN sustainability criteria, it has made concessions and even established the Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition (BRIGC). However, given this optimistic perspective, one has to question whether the UN is mistaken in its unwavering belief in the BRI.

Assimilation or Marginalisation?

Reports on the numerous human rights abuses committed against Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang have been regularly released by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). The birth rate in the area has dropped to half of its 2019 level, and more than a million Uyghurs have been taken into “re-education camps” by force. In Xinjiang, a little over 200,000 IUDs were implanted in 2014. The number increased by 60% to 330,000 IUDs in just 4 years. These figures, along with reports of forced sterilisation in the area, do little to improve the perception of China’s goals in Xinjiang. Fifty-one member countries released a united statement denouncing China’s actions in the region in October 2023.

Notably, nations that expressed their faith in China’s intentions or remained mute were somehow associated with the Belt and Road Initiative. China’s veto participation in the UN Security Council and its menacing tendency towards swiftly allowing China to leave due to advantageous transactions permit a collective “open silence” regarding the Uyghur Muslims. Although the UN has long been positioned as the defender of human rights and the maintenance of peace and security, how can it effectively carry out this role in the case of the Uyghur Muslims when so many factors are at play that make it impossible for it to act impartially and without bias? When it comes to Xinjiang, the group appears to be caught in a conflict of interest that denies the Uyghur people honest and open access to judicial and moral remedies.

Many nations have benefited from the Belt and Road Initiative in terms of multilateral cooperation, international trade, and infrastructure development. It has created pathways for collaboration and connectivity across continents. Its propensity to make many nations dependent on China, however, portends problems for individuals who are persecuted and discriminated against by the Chinese government. This dependence has resulted in an unfair silence within the international community. The plight of the Uyghur Muslims is likely to worsen and recur until the survival of another ethnic minority is compromised in favour of economic prosperity, as China continues to unveil projects that turn Xinjiang into a prosperous moral wasteland that has no room for its original inhabitants. With each passing day, the Uyghurs struggle for a sense of dignity and justice amid the numerous atrocities committed against them.