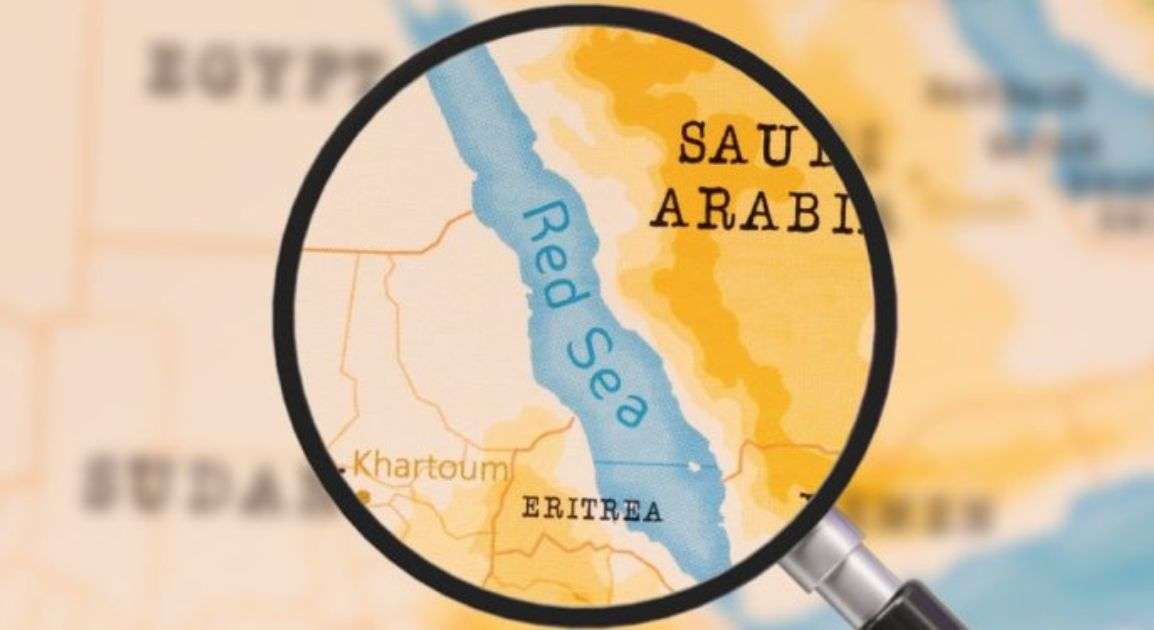

The world’s commerce map is being redrawn—not by trade agreements or technology, but by missiles, drones, and the ongoing instability in one of the world’s most critical waterways. The Red Sea, which has long been a reliable trade route, has become a geopolitical flashpoint. What is taking place there is more than simply another regional battle; it is a structural shift in how global goods, energy, and power are distributed.

The Chokepoint That Holds the World’s Breath

The Red Sea is more than just a sea. It’s a bottleneck. The small length that connects the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean carries 12% of world trade and 30% of container traffic. For decades, this route quietly powered globalization: it was efficient, cost-effective, and reliable. But stability is now considered a luxury.

The escalation of Houthi attacks in Yemen has damaged that foundation. The strikes, which primarily target vessels associated with Israel, the United States, or their allies, have made commercial shipping a high-risk venture. The escalation of Houthi attacks in Yemen has skyrocketed insurance rates, collapsed shipment timetables, and forced businesses to take costly detours. Everyone suffers when the world’s arteries become blocked.

The Cape Detour: Longer, Costlier, and Dirtier

To keep freight moving, maritime companies such as Maersk, MSC, and Hapag-Lloyd have redirected ships around the Cape of Good Hope. The math is brutal: an additional 3,500 nautical miles, up to two weeks at sea, and millions of dollars in fuel, security, and labor costs. For sectors already dealing with inflation and energy insecurity, this has snowballed into a broader economic challenge.

Freight prices between Asia and Northern Europe have already increased since the escalation started. What begins in the Red Sea does not stay in the Red Sea; it spreads to grocery stores, electricity bills, and manufacturing lines across continents.

And don’t overlook the environmental cost. More detours mean more fuel use and emissions—an ironic twist in a world ostensibly moving toward a greener economy.

An Artery Under Pressure

If the Red Sea’s shipping arteries are its veins, then energy is its lifeblood. The Bab-el-Mandeb Strait transports a substantial portion of the Persian Gulf’s oil and LNG. Disruptions here have a direct impact on the European Union’s energy security, which had already weakened following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Tankers are forced to take the longer route around Africa, extending energy delivery timeframes and increasing expenses. For import-dependent economies such as Germany, Italy, and France, the Red Sea represents a new vulnerability. Higher shipping costs lead to higher energy prices, which contribute to inflation. There is no easy way to stop the chain reaction.

Maritime Risk Is Back in the Geopolitical Game

For decades, the world has taken safe maritime routes for granted. Those days are over. The Red Sea crisis has reignited the use of the term “maritime risk” in boardrooms. Insurance rates have risen, shipping companies are rethinking their entire routing plan, and governments are revisiting naval doctrines.

Although the Red Sea is today’s hotspot, it also serves as a warning. Other chokepoints, the Strait of Hormuz, the Malacca Strait, and the South China Sea are now under closer strategic study. One drone strike, one militia raid, one blockade, and global supply routes might be disrupted again. The global economy has become hostage to narrow waters and non-state entities wielding inexpensive but disruptive firepower.

Gunboats and Drones: Limits of Power Projection

The international response has been quick but informative. The US Navy’s Operation Prosperity Guardian, supported by European partners, was intended to secure the lanes. Yet Houthi attacks continue. This isn’t your typical naval combat; it’s asymmetric warfare in a maritime corridor. Drones and anti-ship missiles cost a fraction of the expense of a warship, yet they can bring trillion-dollar trade routes to a halt.

Washington has a strategic quandary: intensify involvement and risk another protracted entanglement, or step back and risk losing influence. For China, which relies on these lanes for exports, the crisis presents an opportunity to expand its maritime security presence, particularly from its base in Djibouti.

Winners and Losers on the New Trade Map

Some people stand to benefit. Ports in South Africa, particularly the Port of Durban, are seeing increased traffic, investment, and geopolitical attention. Energy exporters from the United States, Brazil, and West Africa are becoming viable alternatives to Middle Eastern providers.

Others lose out. Egypt, which relies largely on the Suez Canal for foreign currency, is facing a devastating economic loss. Canal tolls generated more than $9 billion in revenue for the country in 2023. Sustained rerouting could cause a serious hole in its frail economy.

And shipping behemoths face rising operational costs, dwindling profitability, and increased unpredictability. Supply chains designed for just-in-time efficiency are increasingly tripping over just-in-case geopolitics.

India at a strategic crossroads

For India, the Red Sea problem is both a menace and a challenge. Sixty percent of India’s trade with Europe takes this route. Rising shipping costs and delivery delays could lead to domestic inflation and trade imbalances.

However, a crisis can also create opportunities. The volatility makes India’s campaign for the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, which will be revealed during the G20 New Delhi summit in 2023, even more essential and relevant. A safe, diverse connectivity corridor may lessen vulnerability to chokepoints such as the Red Sea. Furthermore, India’s rising naval capacity allows it to play a larger role in regional maritime security. As trade routes become increasingly contested, India’s strategic location becomes its most valuable asset.

Even if the Red Sea cools tomorrow, the world will not resume normal operations. The memory of vulnerability has a lengthy shelf life. Shippers will continue to vary their routes, not for efficiency, but for resilience. Governments will strengthen alliances and naval capabilities. New pathways, including the Cape route, the Northern Sea Route, and overland Eurasian rail networks, will gain strategic importance.

In short, the world is shifting to a post-Suez paradigm, with a logistics map that is no longer anchored in a few stable chokepoints but rather scattered across several, more unstable arteries.

The Red Sea Is a Weathervane

The Red Sea situation is more than just a maritime challenge. It’s a geopolitical weather vane. It foreshadows a world in which non-state actors can interrupt trillion-dollar flows, trade and security are once again inextricably linked, and power will increasingly be evaluated not by who controls markets, but by who can keep sea lanes open.

The Red Sea’s maritime instability is not a temporary blip. It is the new baseline. And the sooner the globe modifies its trade maps, naval strategy, and geopolitical assumptions, the better it will fare in the coming storms.