In the cold desert of Ladakh, silence has always been its own language. It is a silence shaped by the high-altitude winds, by Buddhist monasteries perched on crags, by Muslim hamlets along rivers, by the discipline of mountain survival, and by the rituals of a borderland that has lived at the uneasy edge of empires. Yet today, the silence of Ladakh is not contemplative. It is the silence imposed by curfews, by internet shutdowns, by the choking of dissent, and by the state’s refusal to heed voices that demand recognition. For a region that celebrated its separation from Jammu and Kashmir in August 2019 with the hope that Union Territory status would give it autonomy and dignity, the descent into protest, hunger strikes, and bloodshed is both tragic and revealing. It exposes the fragility of India’s constitutional imagination, the shortsightedness of its centralising impulses, and the incapacity of its rulers to reconcile questions of federalism, ecology, identity, and security into a coherent moral and political vision.

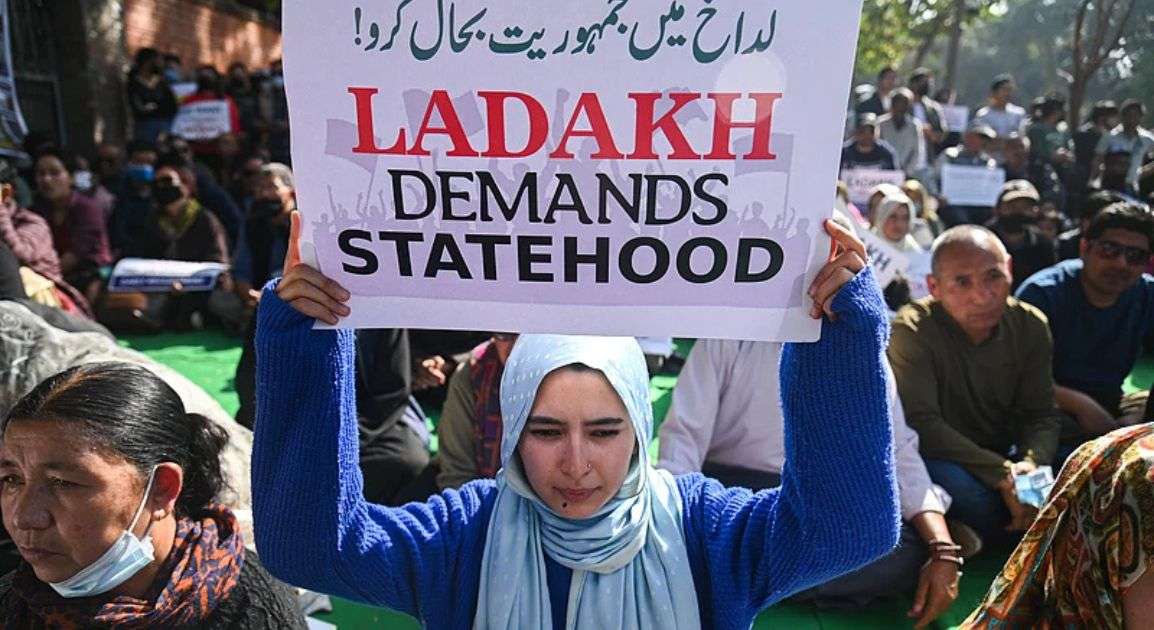

The Ladakh unrest, culminating in the killing of protesters in Leh and the detention of Sonam Wangchuk, is not an episodic disturbance. It is a symptom of a deeper pathology: the Indian state’s inability to deal with dissent except as disorder, its refusal to translate promises into institutional safeguards, and its deep discomfort with giving local communities genuine power over land, culture, and governance. The demand for statehood and inclusion in the Sixth Schedule is not simply a parochial aspiration; it is an articulation of India’s federal crisis. The promise of democracy is not merely periodic elections, but the ability of communities to shape their destinies. When the people of Ladakh ask for constitutional safeguards, they are reminding India that the Union is not a conquest, but a compact.

At the heart of this conflict lies the paradox of post-2019 India. When Article 370 was abrogated and Jammu and Kashmir bifurcated, the move was justified as a triumph of integration. Ladakh, in particular, was promised empowerment through direct Union Territory status. But the deeper meaning of this reorganisation was not empowerment; it was dispossession. It made Ladakh a direct subject of central rule, stripped of legislative power, bereft of representation in its own land, and hostage to bureaucratic fiat. The irony is glaring: the region most celebrated for its patriotic fervour is now the region that feels most alienated from the Republic.

To understand this unrest, one must place Ladakh in its broader contexts.

The first is environmental

Ladakh is one of the most ecologically fragile zones in the world. Its cold desert ecosystem, already under stress from climate change, glacial retreat, and erratic water supplies, has been further destabilised by militarisation, unsustainable tourism, and unregulated infrastructure expansion. Roads cut across sacred landscapes, rivers are diverted, and fragile habitats are bulldozed in the name of connectivity. For Ladakhis, land is not merely property; it is the basis of culture, livelihood, and survival. The fear that their land will be alienated to outside interests-corporates, real estate speculators, mining companies-is not an irrational paranoia. It is a rational response to the state’s track record of turning peripheral geographies into extractive frontiers. The Sixth Schedule demand is, at its core, an environmental demand: a demand to preserve control over land and resources, to ensure that ecological survival is not mortgaged to developmental hubris.

The second context is demographic

For decades, Ladakh’s anxiety has been about being numerically small, vulnerable to the demographic weight of outsiders. The memory of other Himalayan regions, where indigenous communities were marginalised by in-migration and resource grab, haunts Ladakh. The promise of constitutional safeguards is not a xenophobic desire to exclude; it is the minimal requirement for cultural survival. When identity is fragile, and when the state does not inspire trust, the fear of being swamped is real. The protester on the streets of Leh is not fighting against modernity; he is fighting against erasure.

The third context is strategic

Ladakh is India’s front line with China. Its valleys and passes are not just scenic; they are theatres of a great power rivalry. The blood spilled in Galwan in June 2020 was not just a clash of soldiers; it was a brutal reminder that Ladakh’s geography is inseparable from India’s sovereignty. Yet in this very theatre of vulnerability, the Centre has chosen to alienate its own people. By treating Ladakhis as subjects rather than stakeholders, the state weakens its own strategic depth. National security cannot be secured by the barrel of a gun alone; it requires the loyalty, trust, and participation of those who inhabit the borderlands. The Ladakh unrest reveals the strategic shortsightedness of New Delhi: it confuses control with stability, and coercion with loyalty. In doing so, it risks turning the very people who guard the frontier into disenchanted spectators of a republic that ignores their voice.

The fourth context is the politics of Union Territories after 2019

Ladakh’s fate is inseparable from the centralising experiment unleashed after the abrogation of Article 370. The creation of Union Territories was not merely an administrative decision; it was a symbolic assertion of central sovereignty over contested lands. In Jammu and Kashmir, this was framed as the dismantling of an anomaly. In Ladakh, it was framed as recognition. Yet in both cases, the deeper logic was the same: to hollow out federalism, to reduce local political elites into irrelevance, and to turn governance into bureaucratic administration under the direct control of New Delhi. Ladakh is therefore a laboratory for a new kind of politics: where constitutional guarantees are replaced by executive discretion, where dissent is contained through surveillance and curfew, and where the idea of self-rule is dismissed as an obstacle to integration.

The tragedy is that this centralising experiment is self-defeating. A democracy that cannot accommodate the pluralism of its peripheries becomes a brittle republic. Ladakh’s demands are not secessionist. They are within the constitutional framework: statehood, Sixth Schedule, environmental protection, and genuine representation. Yet the state responds with violence, detentions, and token committees. It infantilises Ladakhis, as if they cannot be trusted with their own future. In doing so, it reveals the hollowness of its own democratic commitments. The question Ladakh poses to the Republic is stark: can India be a federation that accommodates diversity, or is it destined to become a centralised state that fears its own citizens?

Moral Dimension

There is also a moral dimension to this crisis. The hunger strike of Sonam Wangchuk is not merely a political tactic; it is a moral indictment of a system deaf to reason. His fasts echo a Gandhian grammar of politics that is alien to the current regime’s imagination. For Gandhi, fasting was not blackmail; it was an appeal to conscience. But in today’s India, conscience has no place in the corridors of power. The detention of Wangchuk, even after deaths on the streets of Leh, is emblematic: the state cannot countenance even the moral power of vulnerability. It prefers silence enforced by law to silence cultivated by trust.

The wider philosophical stakes are profound. Ladakh is not just about Ladakh. It is about what kind of Republic India aspires to be. A Republic that treats its borderlands as expendable zones, whose people are to be disciplined rather than empowered, is a Republic that betrays its own promise. A Republic that ignores ecological fragility, that dismisses cultural survival, and that conflates unity with uniformity is a Republic at war with itself. Ladakh’s silence is therefore not just a regional silence. It is the silence of the Constitution itself, a silence that comes when promises are broken and voices unheard.

To break this silence, India must reimagine its federal compact. Ladakh needs statehood not as a gift, but as a right. It needs Sixth Schedule protections not as charity, but as recognition of its ecological and cultural uniqueness. It needs meaningful representation not as tokenism, but as justice. It needs development that is sustainable, not extractive. It needs a security policy that builds trust, not fear. Above all, it needs a Republic that sees its people as partners, not as subjects.

In the end, the crisis in Ladakh is not about numbers or territory. It is about dignity. A people who live in the harshest of terrains, who have borne the burden of guarding the nation’s borders, who have preserved fragile cultures against overwhelming odds, are asking for recognition. If the Republic cannot grant them that dignity, then its moral claims are hollow. Ladakh reminds us that the measure of a democracy is not how it treats its powerful, but how it treats its smallest, most vulnerable communities. In that test, the Republic has faltered.

The silence of the mountains is waiting. Whether it becomes the silence of resignation or the silence before a storm depends on whether India can rediscover the courage of listening.

The Views and Opinion Expressed in this article are that of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of The Dialectics.