Introduction

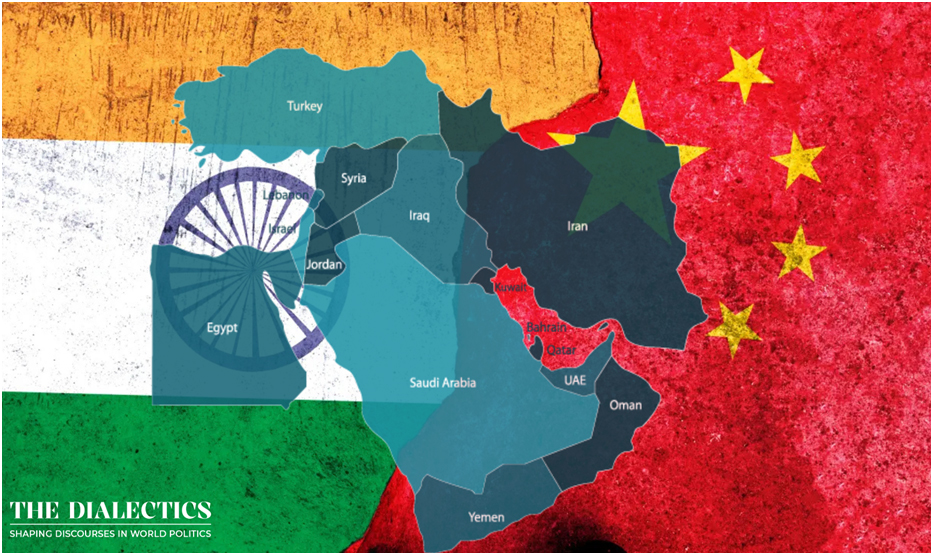

China’s foray into West Asian diplomacy is a paradigm shift in the geopolitics of the region. From being a primarily transactional player in the region, China has moved to that of a peacemaker with a world view, as evident from its unprecedented facilitation of Iran-Saudi peace in 2023. Whereas this might look like a welcome trend in a restive region, it constitutes a very real set of challenges for India. Very far from being neutral or benign, China’s increasing influence—economic, diplomatic, and strategic—undermines India’s presence in a region critical to its energy security, diaspora protection, regional connectivity plans, and increasing global profile. As China consolidates its presence, India stands to be edged out in both symbolism and substance.

Strategic Erosion of India’s Balancing Role

India has historically played the rare role of a trusted interlocutor across hostile divides in West Asia—Iran and Israel, Israel and Palestine, Iran and the Gulf, and even intra-Gulf rivalries. This balancing act gave India a unique diplomatic edge. However, China’s rise as a conflict mediator now monopolises this role.

Through intruding as the favoured interlocutor—owed to its fiscal clout, non-alignment on local politics, and lack of colonial overhang—China diminishes the strategic space for Indian diplomacy. New Delhi, previously regarded as an honest broker, increasingly feels passive or on the periphery.

Erosion of India’s Leverage in Crisis Management

West Asia is not just India’s energy provider but also home to more than 8 million Indian workers. During periods of regional turmoil, such as the Yemen war, Syria, or even recent Red Sea tensions, India had to fall back on its bilateral goodwill to evacuate citizens, handle crises, and secure diaspora rights. As China becomes more central as a regional diplomatic and logistical base, India might find it harder to gain access to crisis corridors, negotiate safeguards, or obtain good results when its citizens are at risk. China’s greater reach among Gulf decision-makers would make Indian appeals less pressing.

Economic Marginalisation in the Gulf and Beyond

India is already falling behind in the main economic spheres. China is the leading trading partner for the majority of West Asian countries and has increased economic interdependence by:

- Belt and Road investments in Iran, Iraq, the UAE, and Egypt

- Port construction projects throughout Oman, Djibouti, and the Suez Canal

- Regional infrastructure, logistics, and AI technology dominance

China’s role as a mediator provides it with even greater soft power to influence economic choices. Indian businesses, which previously had open competition, now risk being shut out of high-stakes ventures because of China’s political influence and integrated investment packages.

India’s connectivity projects, such as IMEC and Chabahar, are being increasingly overshadowed by Chinese corridors. The IMEC itself, which was initiated at the G20, stands to be undercut if China manages to stabilise the region according to its interests and divert energy and trade flows through its own channels.

Weaponisation of Economic Leverage by China

China is not an altruistic actor. Under geopolitical tensions, like the 2020 Galwan standoff, China has applied trade sanctions, digital restrictions, and border coercion to India. With China’s mediating credentials legitimised in West Asia, Beijing may weaponize its leverage over oil supply, financial flows, or access to ports to punish India during periods of bilateral tensions.

Whereas America or the EU keep their economies separate from strategic aspirations, China does not keep its economy separate from strategic ambition. This leaves India exposed, particularly considering its Gulf remittances, oil flows, and port access dependence.

Normative and Ideological Challenge to India’s Global Vision

India positions itself as a civilizational democracy, a bridge between the Global North and South, and an advocate of multipolarity based on democratic values. China’s success in mediation—based on authoritarianism, state capitalism, and “non-interference”—provides a contrasting model that will be more attractive to autocratic Gulf states or sanctioned nations such as Iran.

This normative conflict undermines India’s long-term positioning in the region. As nations increasingly embrace China’s “infrastructure-for-silence” model, India’s value-based diplomacy will become less attractive, particularly on issues like religious tolerance, human rights, and diaspora dignity.

Geopolitical Threat to India’s Maritime Strategy

China’s mediation reinforces its hard power encirclement of India. Beijing’s port footholds in Gwadar, Djibouti, and Oman already afford it control over chokepoints in the vicinity of the Strait of Hormuz, Bab el-Mandeb, and the Gulf of Aden. With diplomacy supporting military reach, China’s dual-use maritime infrastructure is more difficult to challenge. India, whose maritime strategy seeks to project power in the Indian Ocean and West Asia, now sees its strategic depth threatened. The absence of a security or naval pact between India and West Asian powers—compared to China’s military alliances with Iran and port rentals—also adds to this disadvantage.

Diplomatic Crowding-Out in Multilateral Forums

Considering China’s new role as a peace broker, West Asian countries will tend to refer increasingly to Beijing’s position in international forums, including:

- UN resolutions on Palestine, Syria, or Iran

- G20 coordination on energy security

- OIC statements involving Kashmir

India’s ability to shape or rally support on controversial matters might wane, particularly if China employs its influence to safeguard allies or shame India on topics such as CAA-NRC, domestic religious riots, or the Kashmir issue.

Control Over Energy Transition Policy

China’s arbitration in the Gulf is not just about oil—it is about controlling the future of energy. Beijing is heavily investing in:

- Green hydrogen projects in Saudi Arabia and UAE

- EV and battery storage infrastructure in Bahrain and Oman

- Digital and AI control systems for energy grids

India, in its quest for energy transition leadership, may find itself relying on Chinese-controlled supply chains or left out of new emerging energy groupings. This impacts not only economic competitiveness but climate diplomacy, where India hopes to be a leader in the Global South.

Strategic Invisibility in a Region of Critical Importance

In a nutshell, China’s emergence as a mediator is not an Indian stabilising opportunity—it is a strategic trap. It puts New Delhi on notice on all fronts:

Diplomatically, by appropriating its role as a neutral mediator

Economically, by monopolising trade, investment, and connectivity

Militarily, by encircling India with dual-use infrastructure

Ideologically, by peddling a model contrary to India’s vision

Internationally, by rendering India irrelevant in multilateral decision-making on West Asian issues. West Asia is not merely another region for India—it is its energy lifeline, a diaspora remittance source, a springboard for global ambitions, and a centre of its extended neighbourhood doctrine. If China is to become the unchallenged voice of stability and diplomacy in this region, India will be left to respond from the periphery. New Delhi needs to move, through bold diplomacy, strategic infrastructure, diversified alignments, and regional military cooperation, to avoid strategic invisibility in a region at the heart of its emergence.