Significance of folk-practices

A. L. Basham described India, as in truth, a land of contrasts and diversities, a great mosaic in which different elements exist side by side and yet possess a unity which pervades all its varied manifestations.

‘Culture has been referred to as man’s ‘social heritage’ and as ‘the man-made part of the environment, consisting of any form of behavior which is acquired through learning, and which is a pattern in conformity with certain approved norms (William R. Bascom). The core of a culture consists of the shared assumptions, beliefs, and values that the people of a geographical area acquire over generations. In Indian culture, each region has its folk practices, reflecting the traditions and beliefs of the country’s communities, these regional folk practices have been preserved and followed through generations. Folk religion according to Nandini Sahu was subsequently seen as a belief system that occurred in conjunction with established and official religions and mythical practices.

This article presents the significance of folk deities in Indian culture and their distinction from Vedic traditions. It describes the influence of Sanskritisation on their identity and the process that has integrated these deities into a broader religious and social framework. In the Indian cultural milieu, the classical Sanskritic and Brahmanical religious practices have taken centre stage in the religious panoptical system at the cost of marginalisation and suppression of important local and vernacular practices and theories (Sahu 2022: 3).

Marginalisation and Folk Adaptations

The restrictions placed on untouchables and lower castes of India prohibited their entry into temples, and public spaces, and access to religious sermons like the Vedas. In response, socially marginalised groups created their own non-orthodox spiritual practices, influenced by radical sects such as the Charvakas, bhakti traditions, and Nathpanthis (Dhali 2020: 24).

Religiously, the deities of folk traditions are not typically embraced within the Vedic tradition. S. Xavier explains that in a changing economic scenario, the Vedic priests are now ready to serve in these temples. They have adopted various strategies collectively known as ‘Sanskritisation.’ In the Indian Sociological scenario, the term ‘Sanskritisation’ was introduced by M. N. Srinivas. The term refers to a process where the people of lower castes collectively try to adopt upper-caste practices and beliefs to achieve a higher status. This indicates cultural mobility within India’s traditional social system. M. N. Srinivas argues that the lower societal groups are trying to imitate Vedic people. However, S. Xavier, disagreeing with this statement, suggests that the folk people are not voluntarily adopting these practices but are being forced to emulate Vedic customs and attributes (Xavier 2009-2010: 632).

Sanskritization and Integration of folk deities

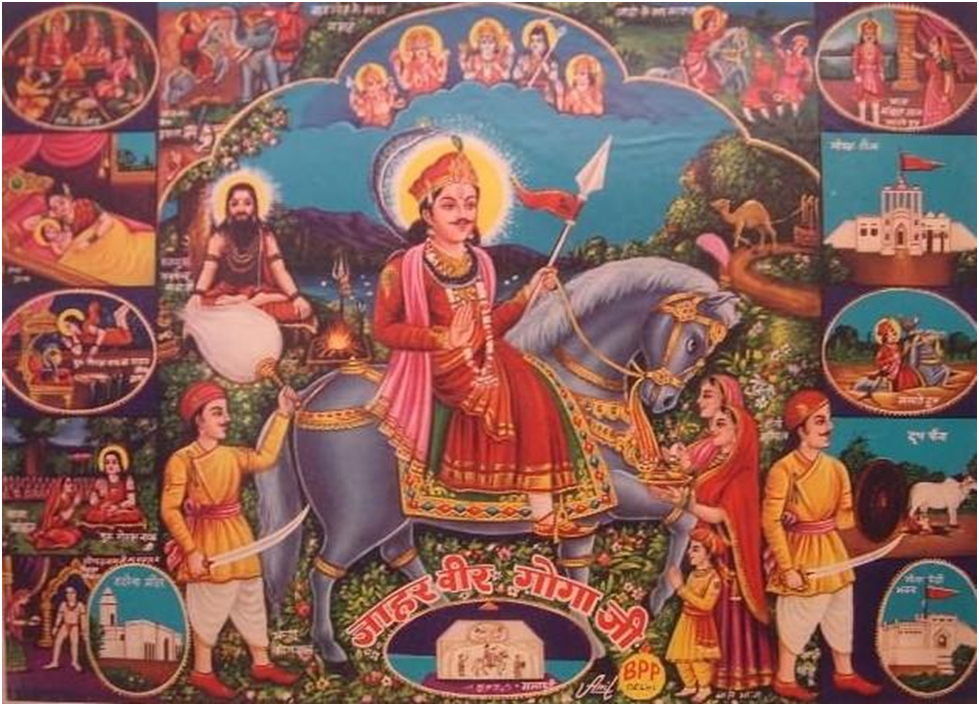

Xavier examines the process of Sanskritisation, a term akin to acculturation, the process by which subordinate groups integrate into the dominant society. For instance, deities from local traditions often merged with major gods and animal totems such as kites, elephants, bulls, serpents, rats, and peacocks have become vehicles or ornaments or parts of bodies of major gods (Xavier 2009-2010: 632). Among all the animals held in worship in India, the serpent is the most important. In North India, the serpent is worshipped as Nagaraja, the king of snakes, while in the South, living snakes are venerated. In Bengal, the anthropomorphic serpent goddess Manasa is widely worshipped, with the Manasa cult particularly popular among Hindus, especially in lower-class communities. Similarly, in Rajasthan, Goga is an important folk deity associated with serpent worship. Revered as a guardian and protector, Goga is believed to safeguard devotees from snake bites and ensure fertility and prosperity.

Hinduisation of Tamil Folk deities

In India, particularly in South India, many folk deities are female and closely linked to the fertility of the land. These deities are often depicted as unmarried young virgins, in contrast to classical female divinities, who are predominantly portrayed as married and nurturing maternal figures. A.K. Ramanujan categorizes female deities into two distinct groups: “tooth goddesses” and “breast goddesses.” The former generally represents folk deities, while the latter aligns more with classical divinities (Ponniah 2006: 11). Additionally, in his another article, Hinduisation of Folk Deities and the Emergence of Hindu Revivalism, S. Xavier explains this process in detail. Folk deities in Tamil literature evolved from the five geographical divisions known as Thinai. Texts like Paripadal and Tirumurukkatruppadai mark the shift from tribal folk worship to formal religious systems, which crystallized under the Pallavas and Pandyas into Puranic Vaishnava and Saiva traditions. This regional synthesis blended local cults with dominant northern Sanskritic elements, merging or integrating folk deities into the Puranic pantheon.

A devotee performing sacrificial acts of carrying kavadi and body piercing towards Lord Muruga

Furthermore, Mayon (Tirumal, with ‘mal” meaning cloud and ‘Thiru‘ meaning sacred in Tamil) was a chief worshipping deity of Vedic Aryans, and was a pre-Vedic and non-Vedic God. Nediyon was the chief deity of the Neithal (Coastal) belt. Nediyon is the god of water (Aazhiyon- God of Sea) he is also called Narayana (Nara– water and Ayana– sleeping). In the Tamil context, Vishnu is not only revered as the God of the Sky but is also known as Mayon or Thirumal, closely associated with rain. Vishnu, along with deities such as Siva, Muruga, Sakthi, Lakshmi, Krishna, and Balarama, is considered to have origins in non-Vedic and pre-Vedic traditions. These deities were initially opposed by the Indo-Aryans and were later incorporated into the Vedic religion. Evidence supporting this can be found in Vedic literature (Xavier 2009: 107).

Scholarly understanding of Hinduism as a systematic religion is likewise shaped by endeavors to construct a uniform, coherent system of beliefs and religious practices. However, the Hinduism of the scriptures is different from the vernacular forms of the religion that are expressed, practiced and narrated by ordinary people, the majority of whom live in the countryside. Processes like Sanskritisation and Hinduisation have integrated folk deities into the mainstream while often marginalizing their original practices and communities.

Folk deities worldwide have been integrated into dominant religions in various ways. In Christian Europe, pagan gods like the Celtic goddess Brigid were reinterpreted as saints, maintaining their original attributes within a Christian framework. Similarly, in Africa, the spread of Islam led to the reinterpretation of local deities as Islamic saints. In the Americas, African deities were syncretized with Catholic saints, allowing them to preserve their cultural significance within a new religious context. These adaptations highlight the resilience of folk beliefs in the face of dominant religious systems. Rooted in local beliefs, these deities reflect the cultural diversity and spiritual resilience of marginalized groups, painting a picture of India’s rich pluralistic heritage. These deities embody the spiritual and cultural practices of marginalized and subaltern communities, offering a unique perspective on India’s religious diversity. Rather than subsuming them under mainstream practices, it is equally important to study and celebrate the worship traditions of tribes and other marginalized groups. The folk deities of India are not mere relics of the past but expressions of local beliefs, and understanding them in their original forms can throw a light on the unknown or less explored aspects of Indian society.