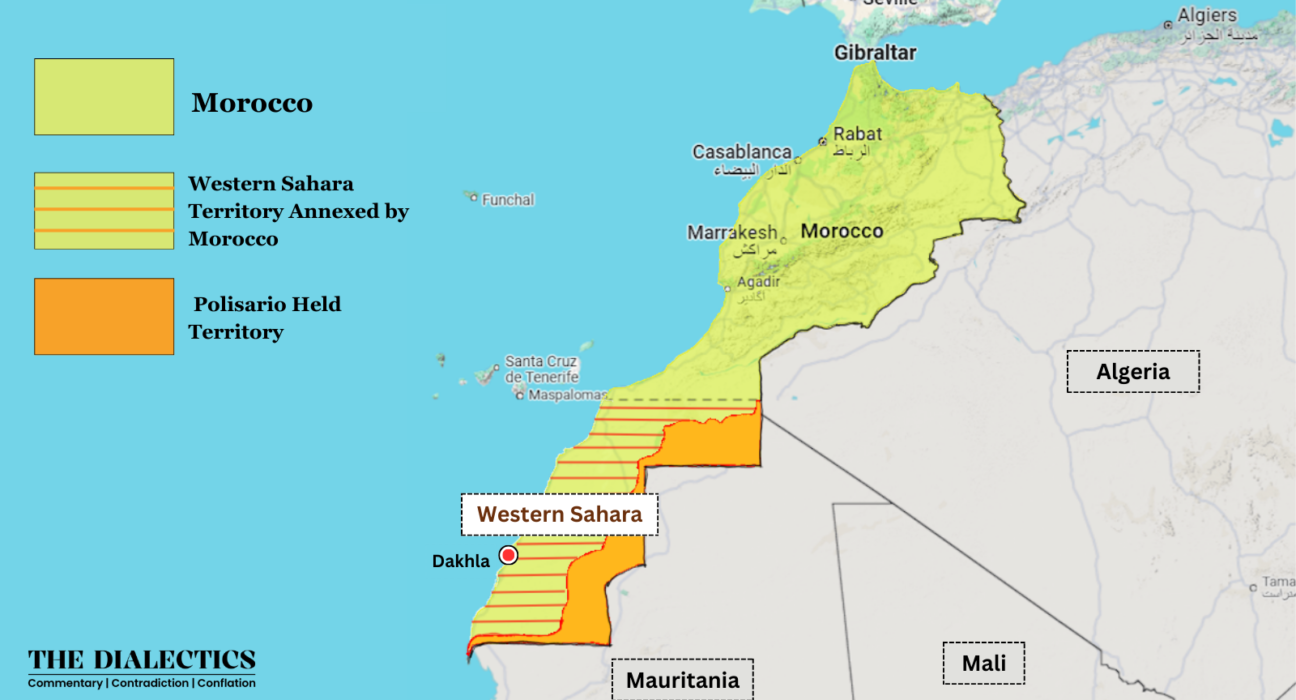

The world’s attention is drawn to the two ongoing wars, and the hope of attaining Self-determination of the once-Spanish colony seems denied. Western Sahara is a disputed territory, located in North Western Africa with Morocco on its North, Algeria to the northeast, Mauritania to the southeast, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. Western Sahara is the last colonial state yet to attain statehood.

This article will help to understand the impasse that has prevailed between Morocco and Western Sahara and the power play since 1975 and how referendums fail when the authority rests in the hands of the powerful which again proves how might is right even if the sidelined party’s case rested on international law and UN resolution, internationally agreed upon principles.

Morocco’s Invasion: Exploitation of Resources and Strategic Value

Morocco’s interest in the former Spanish colony of Western Sahara stems from its abundant resources and geopolitical significance, including rich phosphate reserves and a 700-kilometer Atlantic coastline. Initially supportive of Sahrawi’s self-determination, Morocco shifted to asserting territorial claims once it appeared unlikely that the region would voluntarily integrate with the kingdom. This pivot led to the controversial Madrid Accords in 1975, wherein Spain relinquished control of Western Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania, despite an International Court of Justice (ICJ). Morocco’s subsequent occupation has drawn criticism for violating international norms and exploiting the territory’s natural wealth with external support from the West. The West has also contributed to its exploitation through Morocco’s presence in the disputed land.

Decolonization Denied: The Polisario Front’s Armed Resistance and the Quest for Self-Determination

On November 14, 1975, Spain, Morocco, and Mauritania signed the Madrid Accord, granting Morocco control over the northern two-thirds of the former Spanish colony and Mauritania the southern one-third, despite the International Court of Justice’s restraint. This agreement marked Spain’s failure to fulfill its decolonization obligations, effectively transferring administrative control to the two states. Following Spain’s departure on February 27, 1976, the Polisario Front, representing Western Sahara, declared the creation of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) from exile in Algeria. The SADR, formed on the same day, is now recognized by more than 75 countries. The Polisario Front opposed the Madrid Accord, initiating armed resistance against Morocco and Mauritania. Despite a UN Security Council resolution on November 6, 1975, urging Morocco to withdraw from Western Sahara, Morocco intensified its occupation with military, economic, and political backing from the United States and France. From 1976 to the ceasefire in 1991, Sahrawi combatants, supported by Algeria, waged a prolonged conflict. Mauritania, after occupying the southern territory in 1976, withdrew in 1979, relinquishing its claims. The struggle persisted as Morocco consolidated its control over the region, leaving the Sahrawi people’s quest for self-determination unresolved.

Algeria’s support for Sahrawi self-determination stems partly from its historical tensions with Morocco, rooted in colonial-era disputes and a broader struggle for regional dominance. While Algeria advocates the Sahrawi cause, Morocco’s irredentist ideology and territorial ambitions have shaped its approach. These aspirations reflect a broader contest for influence, with the Western Sahara conflict intensifying the already strained relations between the two neighbors.

Failed Referendums and Stalemates in the 1990s

In the 1991 ceasefire agreement, the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) facilitated a referendum to determine the territory’s future. However, this referendum has never materialized due to Morocco’s consistent obstruction and the tacit approval of its powerful allies. The UN’s efforts to resolve the conflict, including the Houston Accords brokered by James A. Baker in 1997, failed to yield substantive progress. Morocco’s reluctance to conduct a referendum on independence and its insistence on maintaining autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty have perpetuated the deadlock. The cycle of proposing solutions under the cover of illusory autonomy and rejection by either side went on. Meanwhile, international attention had shifted to other crises, such as Iraq, which had further marginalized Western Sahara’s struggle for independence.

The Western Sahara conflict underscores the systemic failures of the United Nations, particularly in upholding its mandate to decolonize non-self-governing territories. Despite decades of resolutions affirming the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination, the UN has been unable to enforce its decisions due to the political interests of member states and the structural limitations of its processes, particularly the veto power in the Security Council. They erode the UN’s credibility, exposing its inability to address conflicts where the interests of powerful states are at stake. This selective enforcement of international law undermines the principles of equity and justice. Countries like France and the United States have frequently leveraged their positions as permanent members of the UN Security Council to shield Morocco from international accountability. France, in particular, has openly declared its intent to use its veto power to block any resolution perceived as unfavorable to Moroccan sovereignty, further stalling progress. In essence, the Western Sahara conflict highlights how the veto power—originally intended to maintain global peace—can be weaponized to prioritize political alliances over the foundational principles of the United Nations. The Sahrawi people’s plight serves as a stark reminder of the need to reform international governance systems to ensure accountability, fairness, and the protection of fundamental human rights. Today, Morocco continues to claim Western Sahara, calling it Morocco’s “southern provinces”. Western Sahara remains an anomaly in UN peacekeeping history as a colonial dispute without a designated administering power.

Trump’s Second Term: Strengthening Morocco’s Position and Diminishing Sahrawi Hopes

In December 2020, the Trump administration made a pivotal policy shift by recognizing Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara, marking a departure from the U.S.’s previous neutrality. This recognition was part of a deal under the Abraham Accords, where Morocco agreed to normalize ties with Israel. The decision, accompanied by plans to establish a U.S. consulate in Dakhla, signalled strong U.S. alignment with Morocco. While celebrated by Morocco, the move faced global criticism for undermining Sahrawi self-determination, ignoring UN resolutions, and prioritizing geopolitical bargains over human rights. It emboldened Morocco’s territorial claims, weakening prospects for a UN-led referendum.

A second Trump presidency could worsen Sahrawi’s prospects for independence. Trump’s transactional diplomacy might further entrench U.S. support for Morocco, with Rabat leveraging its regional importance to secure backing. Trump’s skepticism toward multilateral institutions like the UN could hinder mediation efforts. This could isolate the Sahrawi cause internationally, embolden Morocco’s occupation, and render Sahrawi aspirations for independence increasingly unattainable, overshadowed by global strategic interests.

Conclusion

More than three decades after the Cold War, the conflict remains unresolved, this reflects how power politics can dominate international decision-making, where strategic alliances take precedence over upholding human rights and international law. The Sahrawi people’s aspirations for self-determination, despite being recognized in numerous UN resolutions, have been consistently sidelined by the geopolitical interests of global powers. Morocco’s position is strengthened not just by its allies but also by the lack of effective pressure from international institutions like the UN, which remains paralyzed by the veto powers of key member states.

The humanitarian crisis in the region, marked by the suffering of Sahrawi refugees, remains largely ignored, and the promised referendum for self-determination remains unfulfilled. The failure to resolve this issue highlights the flaws within the current international system, where the interests of powerful states can stifle justice and prolong the suffering of marginalized populations. The Western Sahara conflict serves as a poignant example of how global diplomacy, shaped by self-interest, often neglects the rights of people seeking independence and justice.