The Iranian political system is a unique blend of theocracy and republicanism, officially termed as the “Islamic Republic.” This system emerged following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which overthrew the monarchy of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. The theoretical foundation of this system is primarily based on the concept of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist), developed by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the revolution leader.

Why is Iran an Islamic Republic

The concept of Velayat-e Faqih argues that in the absence of the Twelfth Imam (believed by Twelver Shia Muslims to be in occultation), the governance of the Muslim community should be entrusted to a just and capable Islamic jurist. This jurist, known as the Supreme Leader, is expected to guide the nation in accordance with Islamic principles and laws.

This theory combines elements of Islamic jurisprudence with modern state structures, creating a system where religious authority and political power are intertwined. The Iranian Constitution 1979 (revised in 1989) institutionalised this concept, establishing a framework where Islamic principles and republican elements coexist. The system aims to balance popular sovereignty with divine sovereignty. While it includes elected bodies like the presidency and parliament, ultimate authority rests with the Supreme Leader, who is considered the representative of God and the hidden Imam on earth. The system is designed in such a way that the Shia clergy has unlimited authority in all essential matters. Even elections can not happen without clearance from these clergy.

Institutions of the Iranian Political System:

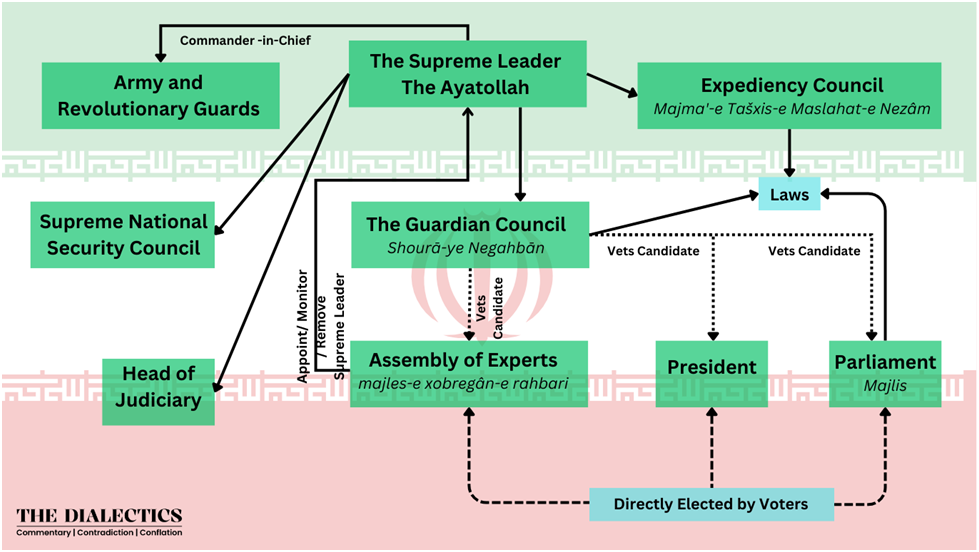

- Supreme Leadership (The Ayatollah): At the apex of Iran’s political structure is the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The Supreme Leader is the highest-ranking political and religious authority in the country. The Assembly of Experts chooses him and holds the position for life. The Supreme Leader’s responsibilities include setting the general policies of the country, serving as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, declaring war or peace, and appointing the heads of the judiciary, state media, and the commanders of the armed forces.

- Executive Branch: The executive branch is headed by the President, who is directly elected by the citizens for a four-year term and can serve for a maximum of two consecutive terms. The President is responsible for enforcing the constitution and serving as the head of the executive, except in matters directly concerned with the Ayatollah. The President nominates ministers who the parliament must approve. The President is responsible for the country’s day-to-day business, but he is not the head of the state.

- Legislative Branch: Iran’s parliament, known as the Islamic Consultative Assembly or Majlis, consists of 290 members elected for four-year terms. The Majlis drafts legislation ratifies international treaties, and approves the country’s budget. The Guardian Council must review all legislation passed by the Majlis (Parliament).

- Guardian Council (Shourā-ye Negahbān): This 12-member body consists of six Islamic faqihs (experts in Islamic Law) selected by the Ayatollah and six jurists nominated by the judiciary and approved by the Majlis. The Guardian Council interprets the constitution and determines if the laws passed by the Majlis are in line with Islamic law and the constitution. It also vets candidates for the Assembly of Experts, the presidency, and the Majlis.

- Assembly of Experts (majles-e xobregân-e rahbari): This elected body of 88 clerics is responsible for appointing the Ayatollah, monitoring his performance, and dismissing him if he is deemed incapable of fulfilling his duties. Members are elected every eight years.

- Expediency Council (Majma’-e Tašxis-e Maslahat-e Nezâm): This administrative Assembly was created by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1988 to resolve conflicts between the Majlis and the Guardian Council. It serves as an advisory body to the Supreme Leader. It has the authority to mediate between the Majlis and the Guardian Council when the two bodies cannot reach an agreement on legislation.

- Judiciary: The judicial system is based on Islamic law and is overseen by the Head of the Judiciary, whom the Supreme Leader appoints. The judiciary is responsible for administering justice, investigating and passing judgment on grievances, supervising the proper enforcement of laws, and prosecuting crimes.

- Armed Forces and Revolutionary Guards: The regular armed forces (Artesh) are responsible for defending Iran’s borders, while the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) protects the country’s Islamic system. Both are under the command of the Supreme Leader.

- The Supreme National Security Council (SNSC): The SNSC central strategic decision-making body in Iran. It is Iran’s top national security body, established in 1989. It determines defence and security policies within guidelines set by the Supreme Leader. The SNSC coordinates political, intelligence, social, cultural, and economic activities related to national security. It also manages resources to address internal and external threats. The council plays a crucial role in protecting Iran’s national interests, Islamic revolution, territorial integrity, and sovereignty. The council is presided over by the president of the country, and the Ayatollah selects the secretary of the Supreme Council.

How the Ayatollah wields Power

Iran has both elected and non-elected branches of institutions, and the unelected branches of institutions are more powerful than the elected ones. The President, Parliament (Majlis) and Assembly of Experts are directly elected, while the powerful clergy appoint the Ayatollah, the Guardian Council and the Expediency Council. The President’s elections are generally free and fair, but the Guardian Council vets all the candidates. The Guardian Council, a 12-member body, consists of six Islamic faqihs (experts in Islamic Law) selected by the Ayatollah and six jurists nominated by the Chief Justice (Who in turn is appointed by the Ayatollah). Hence, the Supreme Leader has direct or indirect control over the Guardian Council, which takes care of elections, vets the candidates and also has veto power over the Majlis (as the Guardian council reviews all legislation passed by the Majlis).

The Constitution requires the Assembly of Experts to select the Ayatollah. Though the Assembly, which also has the right to oversee and remove the Ayatollah, is directly elected, but the candidates must be thoroughly vetted by the Guardian Council, whose members are appointed directly or indirectly by the Supreme Leader.

If legal conflicts arise between the elected Majles and the unelected Guardian Council, the 45-member Expediency Council, which advises the Ayatollah, will have the last say. All 45 members of the Council are appointed by the Ayatollah, who also serves as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. In essence, the Islamic Constitution guarantees that the Ayatollah and the clerical elite maintain solid control over all branches of the state.

The system has faced challenges in balancing Islamic principles with modern governance and popular demands. This had led to periodic tensions, as seen in the 2009 Green Movement protests following disputed election results and the 2017-2018 and 2022 protests over economic issues and women’s rights.

International Perspective:

Internationally, Western nations often view Iran’s political system with scepticism. Critics argue that the system’s theocratic elements undermine true democracy and that the extensive powers of unelected bodies like the Guardian Council limit genuine political competition. However, supporters of the system argue that it provides stability and protects Islamic values while allowing for some degree of popular participation. They contend that the system is uniquely suited to Iran’s cultural and historical context.

Conclusion:

The Iranian political system represents a unique experiment in combining Islamic governance with republican structures. It reflects a complex interplay between religious authority and popular sovereignty, creating a hybrid system that does not neatly fit into traditional categories of governance. While the system has shown resilience, surviving for over four decades despite internal challenges and international pressures, it continues to face questions about its ability to adapt to changing societal expectations and global norms. The ongoing tension between its theocratic and democratic elements remains a defining feature of Iran’s political landscape, shaping its domestic politics and relations with the international community. Understanding this system is crucial for comprehending Iran’s internal dynamics and its approach to international relations. As Iran continues to play a significant role in regional and global affairs, its distinctive political structure will remain a subject of interest and debate for scholars, policymakers, and observers worldwide.