On December 12, 2019, massive protests erupted following the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) on December 11, 2019. The CAA was closely associated with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which was based on 2003 rules. In 2021, the National Population Register (NPR) issue emerged, further linking it to the CAA and NRC, with several states like Kerala opposing it. In March 2024, the notification of the CAA rules sparked protests in Assam. Understanding the connections between the CAA, NRC, and NPR, and how the Assam NRC played a crucial role in fuelling these protests, is now essential.

Understanding Indian Citizenship

The Citizenship Act of 1955 is grounded in Articles 5 to 10 of the Indian Constitution, which establish citizenship criteria for individuals born or residing in India as of January 26, 1950, the Constitution’s commencement date. Article 11 grants Parliament the authority to regulate citizenship rights by law for individuals after the Constitution came into effect, leading to the enactment of the Citizenship Act of 1955

According to the Citizenship Act of 1955, a person can acquire Indian citizenship through several means: by birth, descent, registration (for individuals of Indian origin or with ties to Indian origin), naturalization (for foreign nationals), and incorporation of territory. The conditions for these categories have been revised through various amendments from time to time reflecting evolving policies aimed at regulating the acquisition of citizenship and controlling illegal immigration. One of the requirements for citizenship by naturalization is that the applicant must have resided in India during the last 12 months, as well as for 11 of the previous 14 years.

At present, foreigners and illegal migrants are governed by the Foreigners Act of 1946 and the Passport Act of 1920. Illegal migrants are typically either detained or deported. Under the Citizenship Act, an illegal migrant is defined as a foreigner who:

- Enters the country without valid travel documents such as a passport or visa.

- Enters with valid documents but remains beyond the permitted duration.

CAA 2019

The Act seeks to amend the Citizenship Act, 1955 to make Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian undocumented immigrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, eligible for citizenship of India.

The legislation applies to those who were “forced or compelled to seek shelter in India due to persecution on the ground of religion”. It aims to protect such people from proceedings of illegal migration. The amendment relaxes the requirement of naturalization from 11 years to 5 years on a specific condition for applicants belonging to these six religions. The cut-off date for citizenship is December 31, 2014.The Act says that on acquiring citizenship:

- Such persons shall be deemed to be citizens of India from the date of their entry into India, and all legal proceedings against them in respect of their illegal migration or citizenship will be closed.

The act provides protection to illegal migrants of certain religions from neighbouring countries, with some exceptions for tribal areas in the Sixth Schedule states (Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Tripura) and regions under the Inner Line Permit system. It has faced criticism for excluding Muslim minorities such as Rohingyas, Shia Muslims, Balochis, Ahmadiyya Muslims, and Tamil refugees from Sri Lanka, who are also persecuted minorities.

NPR, NRC and Census The National Register of Citizens (NRC) includes the names and relevant details of Indian citizens, serving as a comprehensive record of the country’s citizens. The NRC was initially compiled following the 1951 Census. It was subsequently updated only for Assam in August 2019. In November 2019, the Home Minister announced plans to extend the NRC to all of India

The National Population Register (NPR) is a database that records all usual residents of the country, including their basic demographic information and biometric details. A “usual resident” for NPR purposes is defined as someone who has lived in a location for six months or more and intends to continue residing there for another six months or longer. The NPR aims to create a comprehensive identity database of all individuals residing in the country. The NPR was first compiled in 2010 and updated in 2015, and it currently includes information on 1.19 billion residents.

The NRC focuses exclusively on citizens of the country and those living abroad, while the NPR encompasses all individuals residing within the country’s territorial boundaries.

NPR vs Census

The Census is governed by the Census Act of 1948, while the NPR is regulated by rules established under the Citizenship Act of 1955. The NPR serves as a comprehensive identity database and its data can be shared with state governments and other government departments. Although the Census also gathers similar information, the Census Act of 1948 prohibits sharing individual data with state or central authorities, allowing only aggregate data at the administrative level to be released.

Additionally, Section 14A of the Citizenship Act of 1955, as amended in 2003, authorizes the central government to create a mandatory register of all Indian citizens and issue identity cards, which pertains to the NRC.

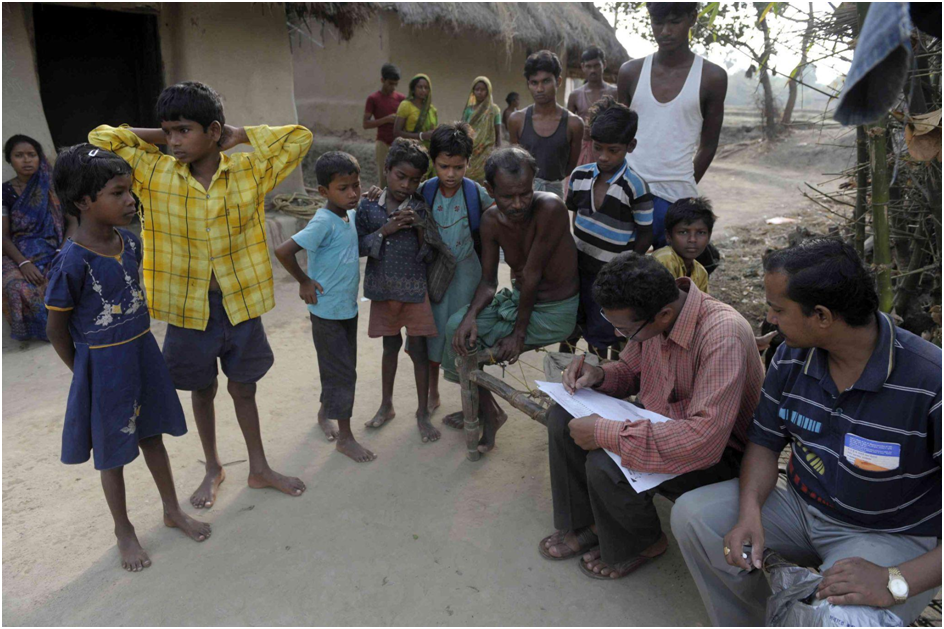

Typically, the NPR is compiled through house-to-house enumeration during the “house-listing” phase of the Census. Consequently, the NPR could serve dual purposes: it could either support the Census of 2021 or function as a database for the NRC in India.

The Assam NRC Since 1950, the influx of migrants into Assam has led to concerns among the original inhabitants about losing their cultural identity and altering the state’s demographics. In the late 1970s, university students in Assam, along with the All-Assam Students’ Union, launched the Assam Agitation, which called for the identification and deportation of illegal migrants in the state. As a result, the Assam Accord was signed in 1985.

The Signing of Assam Accord

According to the Accord, individuals who entered Assam between January 1, 1966 (inclusive), and midnight on March 24, 1971, were to be identified in accordance with the Foreigners Act, 1946, and the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964. The names of such foreigners would be removed from the electoral rolls, and they would need to register with the Registration Officers of their respective districts under the Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939, and its rules. Those who arrived in Assam on or after March 25, 1971, would continue to be identified, removed, and expelled according to the law. Additionally, the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act, 1983, was enacted to support this process.

The implementation of the Assam Accord faced numerous challenges, leading to significant legal issues and even violence, such as a deadly mob attack at the Deputy Commissioner’s office in Barpeta. In 2009, an NGO called Assam Public Works filed a petition with the Supreme Court, seeking the identification and deportation of illegal Bangladeshi immigrants in Assam and the removal of their names from the voter list.

In 2013, the Supreme Court directed that the NRC update be completed by December 31, 2017. However, the final NRC list was released in August 2019, which excluded 19 lakh individuals out of a total of 3.3 crore people. This list, which included Bengali Hindus, Muslims, and other minorities, led to significant discrepancies and controversies.

Timeline

1951: First NRC compiled.

2003: Citizenship Rules introduced, governing NRC and NPR.

2010: First NPR compiled.

2015: NPR updated.

June 2019: Foreigners Tribunals established across India with increased powers.

August 2019: Final NRC for Assam released.

November 2019: Home Minister announces intention to implement NRC nationwide in Parliament.

December 2019: CAA passed, leading to widespread protests.

March 2024: CAA rules released.

Future: NPR to be undertaken alongside the Census.

Currently: No decision yet on a nationwide NRC; Home Ministry provides clarification in Parliament.

Connecting the Dots – NRC, NPR, CAA and Protests

The Assam NRC update excluded 19 lakh people, including Bengali Hindus, Muslims, and other minorities, leading to significant discrepancies and concerns about the accuracy and fairness of the process.

The NPR is a precursor to the NRC and is used for house-to-house enumeration, which facilitates the compilation of the NRC. There are concerns about the NPR being used to support the NRC process, potentially leading to widespread exclusion of residents who may struggle to prove their citizenship.

Critics argue that the CAA, when combined with the NRC, could disenfranchise Muslim communities, as the CAA provides a legal route to citizenship for non-Muslims but not for Muslims who may be excluded by the NRC. The CAA has been criticized for being discriminatory and not providing protection to persecuted Muslim minorities such as Rohingyas and others, leading to nationwide protests.

Protests have continued due to fears that the NPR and NRC processes, coupled with the CAA, might undermine the rights of certain communities and exacerbate issues of statelessness and discrimination.

Thus NRC, NPR, and CAA are interlinked as part of a broader framework addressing citizenship and residency, with the potential for significant implications for individuals’ legal status. The controversies surrounding these measures have led to widespread protests, reflecting deep concerns about their impact on minority communities and the principles of equality and justice.

The Challenges and Limitations

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) has been criticized for its discriminatory nature against Muslims. It provides protection to Hindus excluded from the Assam NRC list but does not extend similar protections to Muslims. Human Rights Watch found that the NRC process in Assam lacked standardization, leading to arbitrary and discriminatory decisions by officials.

The NRC’s verification process applied more stringent documentation standards to ethnic Bengali minority groups, who were often suspected of being “non-original” inhabitants. This approach failed to consider that poorer residents, who often survive on minimal resources, may lack access to the necessary documentation to substantiate their citizenship claims, especially if such documents date back decades. Additionally, Foreigners Tribunals, which adjudicate citizenship issues, have been criticized for their lack of transparency and inconsistent procedures. Activists and journalists have reported that Muslims are disproportionately targeted and declared foreigners compared to Hindus, suggesting possible political influence and bias in the decision-making process.